Table of Contents

The graveyard of innovation is filled with pioneers who arrived first but left forgotten. They had the vision, the timing, the technology. What they lacked was something more fundamental: legitimacy.

We worship first movers in business culture. The mythology runs deep. Be bold. Move fast. Break things. Get there before anyone else and claim the territory. But this narrative ignores a stubborn reality. Most successful innovations aren’t adopted because they arrived first. They’re adopted because people believed in them.

Consider the videophone. AT&T introduced the Picturephone in 1964, decades before Zoom or FaceTime existed. The technology worked. The vision was clear. Yet it failed spectacularly. People didn’t trust that they needed video calls. They didn’t trust the privacy implications. They didn’t trust that the technology justified the cost. AT&T had timing and technology but no legitimacy. Fifty years later, a global pandemic would create that legitimacy overnight, and suddenly everyone was on video calls.

The lesson isn’t about patience or waiting for the right moment. The lesson is that innovation exists in a social context, and that context determines whether your brilliant idea becomes transformative or becomes a cautionary tale in a business school lecture.

The Legitimacy Problem

Legitimacy is the social permission to exist and operate. It’s the collective agreement that something makes sense, belongs, and deserves attention. For innovations, legitimacy determines whether people will trust you enough to change their behavior.

This matters because all innovation asks people to abandon something familiar for something uncertain. You’re asking them to take a risk. The newer and more disruptive your innovation, the bigger the risk you’re asking them to take. Without legitimacy, that risk feels irresponsible. With legitimacy, it feels progressive.

The smartphone didn’t take off because it was the first mobile internet device. It took off because Apple had built enough legitimacy through the iPod that people trusted them to reimagine phones. The Newton, Apple’s earlier attempt at mobile computing, failed partly because Apple hadn’t yet earned that specific legitimacy. Same company, similar vision, different levels of trust.

This isn’t about marketing or persuasion. Legitimacy runs deeper than advertising. It’s about fitting into existing mental models while gently expanding them. It’s about having the right endorsements, the right associations, the right narrative at the right time.

Three Types of Innovation Legitimacy

Not all legitimacy works the same way. Innovations need to establish trust along different dimensions depending on what they’re trying to change.

Pragmatic legitimacy asks: does this actually work? Early personal computers struggled here. They crashed constantly. They were difficult to use. The technology clearly had potential, but it wasn’t yet reliable enough for most people to trust their work to it. Companies that focused obsessively on reliability, like IBM initially, built pragmatic legitimacy faster than those focused purely on features.

Moral legitimacy asks: is this right? Social media platforms are losing this battle in real time. The technology works. The business model works. But growing numbers of people question whether these platforms should exist in their current form. They’re losing moral legitimacy, and no amount of technical innovation can compensate for that loss.

Cognitive legitimacy asks: does this make sense? This is perhaps the hardest barrier for truly novel innovations. The microwave oven needed decades to achieve cognitive legitimacy. People didn’t understand why they would want to cook with radiation. The technology worked, but it violated people’s mental models of how cooking should happen. Only after years of education, demonstration, and gradual exposure did microwaves become a normal part of kitchens.

Most failed innovations had one or two of these forms of legitimacy but not all three. The Segway had pragmatic legitimacy—it worked as advertised. It had cognitive legitimacy among tech enthusiasts who understood personal transportation devices. But it never achieved moral or social legitimacy. Using one in public felt ridiculous. That feeling mattered more than the engineering.

The Chicken and Egg Problem

Here’s where it gets tricky. You can’t build legitimacy without adoption, but you can’t get adoption without legitimacy. This circular problem kills many innovations that arrive too early.

Electric cars faced this for decades. They couldn’t achieve legitimacy because too few people drove them, but people wouldn’t drive them because they lacked legitimacy. The infrastructure wasn’t there because demand wasn’t there, and demand wasn’t there because infrastructure wasn’t there. Technology alone couldn’t break this cycle.

Tesla didn’t solve this with better batteries, though better batteries helped. They solved it by targeting a market segment that didn’t need broad legitimacy: wealthy early adopters who valued status and environmental signaling. This created a beachhead of legitimacy that gradually expanded. The cars became cool, then practical, then normal. But it took twenty years and billions of dollars.

Most innovators don’t have billions of dollars or twenty years. They need to find other paths to legitimacy. This often means piggybacking on existing legitimate categories, even if it means initially mislabeling your innovation.

Early automobiles were called “horseless carriages” because horses and carriages had legitimacy. The name was technically absurd, but it was socially necessary. It gave people a mental hook. Only after cars established their own legitimacy could they drop the reference to the thing they were replacing.

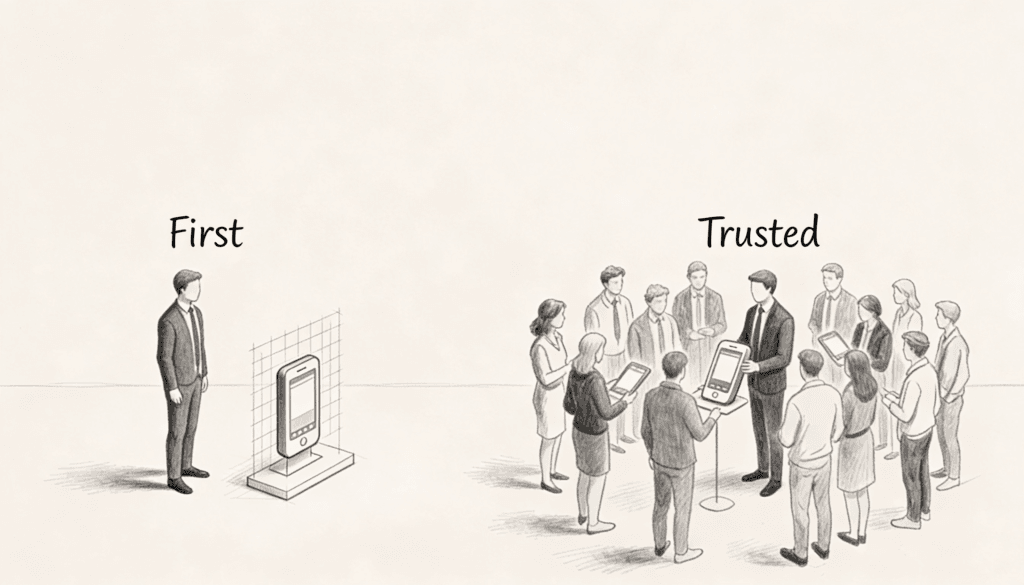

Why Second Movers Often Win

The pattern repeats across industries. Google wasn’t the first search engine. Facebook wasn’t the first social network. The iPhone wasn’t the first smartphone. What these second or third movers had was better timing for legitimacy.

Google arrived when people already understood they needed search but were frustrated with existing options. That frustration created an opening. Facebook launched when college students already understood social networking from Friendster and MySpace. The category had legitimacy; Facebook just executed better within it.

Being first means you have to create legitimacy for an entire category while also competing for adoption. Being second means someone else has already fought that battle. You can focus on execution and improvement instead of explanation and justification.

This doesn’t mean first movers always lose. It means first movers face a different, often harder challenge. They’re not just competing with alternatives. They’re competing with inertia and skepticism.

Networks and Legitimacy

Some innovations face an additional challenge: network effects. The product becomes more valuable as more people use it, but people won’t use it until it’s valuable. This creates an even steeper legitimacy curve.

The fax machine took decades to reach critical mass. Each fax machine was useless until enough other people had fax machines. Early adopters were buying future utility, betting that legitimacy would eventually arrive. Most people rationally waited. Only when businesses started requiring fax numbers did legitimacy snowball.

Cryptocurrency faces this challenge now. The technology works, more or less. The vision is clear. But it lacks the legitimacy needed for mainstream adoption. Most people don’t trust it. Governments don’t trust it. It exists in a strange zone of partial legitimacy—legitimate enough to attract billions in investment, but not legitimate enough to replace actual currency for most transactions.

The technology might be revolutionary, but revolution without legitimacy is just chaos.

Borrowing Legitimacy

Smart innovators don’t build legitimacy from scratch. They borrow it.

Partnering with established institutions transfers their legitimacy to you. When credit card companies first tried to convince retailers to accept cards, they struggled. Too new, too risky, too much hassle. Then they partnered with airlines for frequent flyer programs. Airlines had tremendous legitimacy. If airlines trusted credit cards, maybe retailers should too. The borrowed legitimacy opened the door.

Academic research provides another form of borrowed legitimacy. A technology backed by studies from prestigious universities carries more weight than the same technology without that backing. The research might be preliminary or limited, but the association with academic rigor transfers trust.

Celebrity endorsements work similarly, though more crudely. The celebrity’s legitimacy rubs off on the product. This seems shallow, but it reflects a deep social truth: we trust things that people we trust vouch for. Humans are social learners. We look for signals about what’s safe to adopt.

Regulations can paradoxically create legitimacy. Industries often lobby for regulations that raise barriers to entry because those regulations signal legitimacy. “FDA approved” means something. It means an institution you trust has verified claims. That trust enables adoption.

When Legitimacy Fails

Sometimes innovations never achieve legitimacy, regardless of merit. The technology works, the timing seems right, but trust never materializes.

Nuclear power faced this. After accidents at Three Mile Island, Chernobyl, and Fukushima, it lost moral legitimacy in many countries despite being arguably safer and cleaner than fossil fuel alternatives. The fear became embedded in culture. No amount of evidence or engineering could restore trust. The legitimacy gap was emotional and social, not technical.

Genetic modification of food faces similar challenges. The science is sound. The benefits are real. But GMOs never achieved legitimacy with large segments of the population. The framing was wrong from the start. Instead of emphasizing benefits, the conversation focused on risks. Once that frame solidified, changing it became nearly impossible.

This reveals something important: legitimacy isn’t purely rational. It’s built from associations, feelings, stories, and tribal affiliations. You can’t logic someone into trusting something their community has deemed untrustworthy.

The Speed Paradox

Moving too fast can destroy legitimacy. This seems to contradict the move fast ethos of tech culture, but it’s true.

When Uber and other gig economy companies expanded rapidly, they outpaced their social license to operate. They achieved market presence but not legitimacy. Cities pushed back. Regulators pushed back. The public conversation turned negative. They had to slow down, negotiate, adapt. Their initial speed created a legitimacy deficit they’re still paying off.

Contrast this with how Airbnb eventually approached legitimacy. After initial conflicts with cities, they started working with regulators, collecting hotel taxes, sharing data. They deliberately slowed their approach in new markets to build legitimacy first. This cost them some growth speed but gave them sustainable presence.

The lesson isn’t that speed is bad. It’s that speed without legitimacy is borrowing from your future. Eventually the bill comes due.

Building Legitimacy Deliberately

If legitimacy is this important, can you engineer it? Partially.

Start small and specific. Trying to achieve broad legitimacy immediately is nearly impossible. Find a niche where your innovation already makes sense. Build legitimacy there. Let it radiate outward. Medical innovations often start in research hospitals before moving to general practice. Software innovations start with tech companies before reaching mainstream businesses. This isn’t just about early adopters. It’s about building proof points in legitimate contexts.

Tell the right story. The narrative around your innovation shapes how people evaluate it. Is it a luxury or a necessity? A tool or a toy? A revolution or an evolution? These framings determine who will trust it and why. The story should expand people’s thinking just enough to accommodate your innovation without breaking their existing worldview entirely.

Show the evidence. Legitimacy often requires proof. Not just that the technology works, but that it delivers promised benefits in real contexts with real people. Case studies matter. Testimonials matter. Third party validation matters. This is obvious but often executed poorly. The evidence needs to address the specific doubts your audience holds.

Be patient with culture. Cultural legitimacy takes time. You’re asking people to update their mental models and social practices. That happens slowly. Trying to force it faster often backfires. ATMs took twenty years before people trusted them with their money. You might not have 20 years, but recognizing that legitimacy has its own timeline helps you plan realistically.

The Trust Economy

We live in an economy increasingly built on trust and legitimacy rather than pure functionality. Products often work similarly. Services deliver comparable results. What differentiates them is trust.

People don’t choose the best product. They choose the product they trust enough to try. Then they stick with it unless given strong reasons to switch. This means the first product to achieve legitimacy in a space often maintains advantage even if better alternatives emerge later.

This shifts the innovation game. Technical superiority matters less than it used to. Speed to market matters less than it used to. What matters is speed to legitimacy. How quickly can you become trustworthy? How efficiently can you build social permission?

The answers depend on your specific context. A medical device needs different legitimacy than a social app. But the underlying principle holds: innovation without legitimacy is just an interesting idea. Innovation with legitimacy changes the world.

Moving Forward

If you’re building something new, ask yourself these questions honestly. Do people understand why this should exist? Do they trust that it works? Do they trust that it’s right? Do they trust the people behind it?

If the answers aren’t yes, your priority isn’t building more features or moving faster. Your priority is building legitimacy. That might mean partnering with established players. It might mean starting smaller than you wanted. It might mean telling a different story or targeting a different audience first.

The graveyard of innovation is full of pioneers who got there first but couldn’t convince anyone to follow. Don’t join them. Build something people trust, not just something new.

Being first gives you a head start. But legitimacy determines whether you finish the race.