Table of Contents

We’ve all been there. Someone proposes an idea in a meeting, and before they finish their sentence, another person jumps in with why it won’t work. Then someone else chimes in with a vaguely related tangent about budget constraints. Meanwhile, the optimist in the corner tries to salvage things with forced enthusiasm, and the designated skeptic crosses their arms and waits to demolish whatever survives—clearly, we could all benefit from the Six Thinking Hats approach to structured discussion.

By the end, the idea lies in pieces on the conference room floor, and everyone walks away feeling like they participated in something productive. They didn’t.

This is the modern meeting in its natural habitat: a gladiatorial arena where ideas go to die, dressed up as collaboration. We’ve convinced ourselves that gathering smart people in a room and letting them talk will produce innovation. It doesn’t. It produces noise.

The problem isn’t that people disagree. Disagreement is useful. The problem is that everyone is thinking in different directions at the same time, like an orchestra where half the musicians are playing jazz, the other half are playing death metal, and the conductor has left the building.

The Brain’s Messy Democracy

Your brain, remarkable as it is, makes terrible decisions when it tries to do everything at once. Neuroscience has shown us that different types of thinking activate different neural networks. When you’re being creative, certain regions light up. When you’re being critical, different ones take over. When you’re trying to do both simultaneously, your brain essentially gets into an argument with itself.

Now multiply that chaos by eight people in a meeting room.

What typically happens is that the loudest voice wins, or the most senior person’s opinion becomes gravity, pulling all other thoughts into its orbit. The creative thinkers get shut down by premature criticism. The analytical minds dismiss emotional considerations. The cautious voices smother risk taking before it can breathe.

This isn’t collaboration. This is cognitive collision.

The Colored Hat Revolution

In 1985, Edward de Bono introduced a method so simple it sounds almost childish: Six Thinking Hats. The premise is deceptively straightforward. Instead of everyone thinking in every direction simultaneously, what if everyone thought in the same direction at the same time?

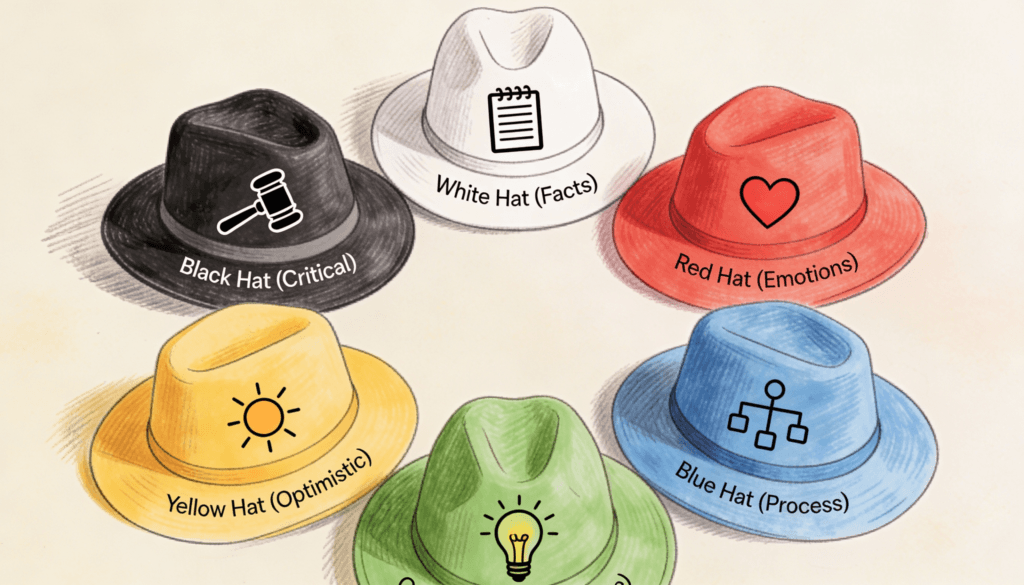

Each hat represents a different mode of thinking. White for facts and information. Red for emotions and intuition. Black for caution and risks. Yellow for optimism and benefits. Green for creativity and alternatives. Blue for process and control.

The genius isn’t in the hats themselves. The genius is in the separation.

When everyone wears the same hat at the same time, something remarkable happens. The cognitive traffic jam clears. The contradictions vanish. The person who usually plays devil’s advocate gets to be wildly optimistic for ten minutes. The eternal optimist gets to voice concerns without feeling like a traitor to their nature.

It sounds too neat. Too organized. Too unlike the messy reality of how breakthroughs actually happen, right?

Wrong.

Why Organized Chaos Beats Pure Chaos

Think about improvisation in jazz. To an untrained ear, it sounds completely spontaneous and free. But jazz musicians will tell you that the best improvisation happens within structure. There are rules, scales, rhythms. The structure doesn’t constrain creativity. It liberates it by providing a foundation from which to leap.

The Six Thinking Hats work the same way. The structure doesn’t stifle thinking. It channels it.

Consider what happens in a typical brainstorming session. Someone suggests using artificial intelligence to personalize customer emails. Immediately, three things happen at once: Someone gets excited about the possibilities. Someone worries about privacy concerns. Someone questions whether the budget exists.

All valid thoughts. All important. All completely destructive when they happen simultaneously.

The creative person feels attacked and stops sharing. The worried person feels ignored and digs in harder. The budget conscious person feels like the only adult in the room. The idea gets dropped, not because it was bad, but because the timing of the thinking was chaotic.

Now imagine the same scenario with structured thinking. First, everyone wears the White Hat. What do we actually know about AI personalization? What data do we have on customer response rates? What do competitors do? Pure information, no judgment.

Then the Green Hat. Everyone becomes a creator. Wild ideas flow. What if the AI could detect customer mood from their browsing patterns? What if it composed emails in the style of their favorite authors? No criticism allowed. Just possibility.

Next, the Yellow Hat. Everyone becomes an optimist. What could go right? How could this transform customer relationships? What benefits might we not have considered?

Then the Black Hat. Now everyone becomes cautious. What are the risks? Where could this fail? What regulations might we violate? But here’s the key: everyone does this together. The natural optimists don’t feel defensive when they point out flaws, because right now, finding flaws is the job. And the natural skeptics don’t feel like party poopers, because everyone is being cautious together.

The Red Hat brings in gut feelings. How do we feel about this? Does something feel off, even if we can’t articulate why? Intuition gets a seat at the table without having to justify itself.

Finally, the Blue Hat ensures the process stays on track and summarizes what was learned.

By the end, you’ve thought about the idea from six distinct perspectives, with full attention to each. And more importantly, you’ve done it without the cognitive whiplash that comes from switching between modes every thirty seconds.

The Counterintuitive Truth About Creativity

Here’s something that catches people off guard: constraints boost creativity, not limit it.

Studies in cognitive psychology consistently show that completely unbounded creativity is actually less productive than creativity within parameters. When you tell someone to “draw anything,” they often freeze. When you tell them to “draw a building that captures sadness,” suddenly ideas flow.

The Six Thinking Hats provide creative constraints. But unlike traditional constraints that limit what you can think about, these limit how you think at any given moment. And that limitation is precisely what makes thinking more powerful.

It’s similar to how weight training works. You don’t build muscle by doing whatever random movements you feel like. You build it through structured resistance. The structure amplifies the effect.

Where Meetings Go to Die

Most organizations treat meetings as necessary evils. They schedule them, attend them, and forget them. Nothing changes. No decisions stick. The same conversations happen in different rooms with different people.

The problem isn’t meeting frequency. Google famously has lots of meetings. So does Pixar. The problem is meeting quality.

Bad meetings are characterized by several features: unclear objectives, dominant personalities, premature criticism, tangents that lead nowhere, and decisions that somehow unmake themselves by the following week.

The Six Thinking Hats address almost all of these. The objective becomes clear because you know which hat you’re wearing and why. Dominant personalities lose their edge because everyone is following the same thinking mode. Premature criticism becomes impossible because criticism has its own designated time. Tangents get caught by the Blue Hat. And decisions stick because they’ve been examined from every angle.

The Practical Application

Let’s be concrete. You’re launching a new product feature. Your team meets to discuss it.

Traditional approach: Two hours of mixed thinking. Some excitement. Some worry. Some random facts thrown around. Someone mentions a competitor. Someone else derails things by bringing up a completely different feature. The meeting ends with vague agreement to “explore this further.” Nothing happens.

Six Hats approach:

White Hat, fifteen minutes. What do we know? Our current feature usage is at 60 percent. Customer surveys show interest in better customization. Development estimates four months. Budget is set. No opinions, just data.

Green Hat, twenty minutes. Everyone unleashes creativity. The feature could adapt to user behavior. It could integrate with third party tools. Maybe it should be modular. What if users could build their own versions? Ideas flow without judgment.

Yellow Hat, fifteen minutes. The team explores benefits. This could increase retention by 20 percent. It might attract enterprise clients. Users might become advocates. Revenue projections look good.

Black Hat, twenty minutes. Now the concerns. Four months might be too long. Competitors might launch first. The technical complexity is higher than estimated. Support costs could spike. Security implications need review.

Red Hat, ten minutes. How does everyone feel? The tech team feels excited but nervous. The marketing team has gut concerns about messaging. The CEO feels this is the right direction despite the risks. Feelings are valid data.

Blue Hat, ten minutes. Summarize what was learned. Decide next steps. Assign responsibilities. Set follow-up dates.

Total time: ninety minutes. Result: a decision informed by comprehensive thinking, with clear next actions, and team alignment on both opportunities and risks.

The Resistance You’ll Face

People will resist this method. Not because it doesn’t work, but because it feels artificial. We’re trained to see organic, free-flowing conversation as superior to structured dialogue. We mistake structure for rigidity.

Some will say it’s too slow. Actually, it’s faster. When you account for all the follow-up meetings needed to revisit unclear decisions, all the conflicts that arise from feeling unheard, and all the ideas that die from premature criticism, structured thinking saves massive amounts of time.

Others will say it feels forced. Yes, at first. So does learning any new skill. Playing piano feels forced until it doesn’t. Swimming with proper technique feels awkward until it becomes natural.

The real resistance often comes from those who benefit from chaotic meetings. If you’re the loudest voice in the room, structure threatens your dominance. If you’re good at political maneuvering, clear process reduces your advantage. The Six Thinking Hats democratize thinking, and not everyone wants democracy.

Beyond the Meeting Room

The interesting thing about training your brain to separate types of thinking is that it becomes useful everywhere, not just in formal meetings.

When you’re stuck on a personal decision, you can mentally wear different hats. Should you take that job offer? White Hat: what are the facts about salary, responsibilities, growth potential? Green Hat: what creative possibilities does it open? Yellow Hat: what’s the best case scenario? Black Hat: what could go wrong? Red Hat: how does it feel in your gut?

Writers use this method without knowing it. First draft is pure Green Hat creativity. Editing is Black Hat criticism. Considering the reader’s experience is Yellow Hat optimism about connection. Understanding the market is White Hat data.

Even arguments with family or friends improve when you can mentally separate emotional response (Red Hat) from factual accuracy (White Hat) from worst case fears (Black Hat).

The Innovation Paradox

The organizations that need structured thinking the most are often the ones most resistant to it.

Struggling companies become desperate for innovation but cling to chaotic brainstorming because it feels creative. They confuse activity with progress. Meanwhile, highly innovative companies like Amazon, Apple, and IDEO use rigorous thinking processes. They know that breakthrough ideas don’t emerge from freestyle chaos. They emerge from disciplined exploration of possibility.

The Six Thinking Hats aren’t about making meetings more corporate or bureaucratic. They’re about making thinking more effective. They’re about creating space for every type of intelligence in the room to contribute fully without being drowned out by incompatible modes of thought happening simultaneously.

Your meetings are killing your ideas because different types of thinking are assassinating each other before any single thought can fully develop. The cure isn’t to think less or meet less. It’s to think more clearly by thinking one way at a time.

The next time you’re in a meeting where an idea gets shot down before it’s fully born, ask yourself: what if we all wore the same hat? What if we gave each type of thinking its moment? What if we stopped trying to think about everything all at once?

The answer might be simpler than you think. Sometimes the most sophisticated solution is just deciding to think about one thing at a time.

That’s not a limitation. That’s clarity. And clarity is where innovation actually lives.