Table of Contents

The conference room is dark. Someone fidgets with the projector cable. Thirty slides are queued up, each one a colorful tombstone for an idea that will never see daylight. You’ve seen this movie before. We all have.

Innovation dies in PowerPoint the way vampires die in sunlight. Quickly, predictably, and with everyone pretending to be surprised.

The strange thing is that we keep doing it. We take our most fragile, most promising ideas and we strap them to a medium designed for sales pitches and quarterly reviews. Then we wonder why nothing changes.

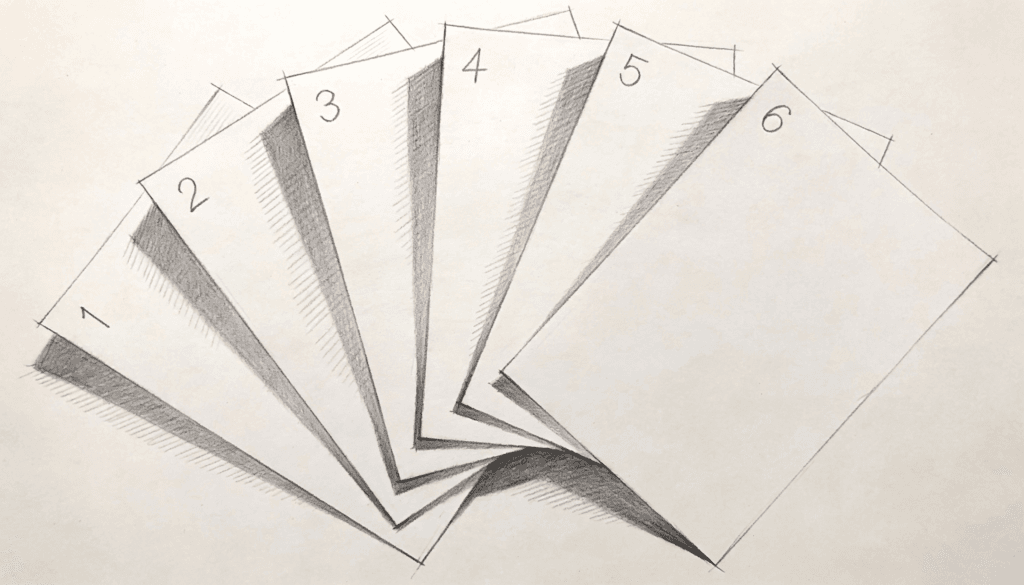

Amazon figured this out years ago and did something most companies consider unthinkable. They banned PowerPoint from innovation meetings and replaced it with something that sounds almost prehistoric: written documents. Specifically, six page narratives that force you to think like a writer instead of a presenter.

The method is deceptively simple. Before any major innovation decision, someone writes a six page memo. Not six slides. Not a six page deck with pretty pictures. Six pages of actual sentences and paragraphs, written in narrative form, explaining the idea from top to bottom.

Then, in the meeting, everyone sits in silence for thirty minutes and reads it. No presenting. No performing. Just reading and thinking.

When Jeff Bezos announced this change, people thought he was crazy. Meetings are already too long. Writing takes forever. Nobody reads anymore. But Amazon persisted, and the results spoke for themselves. AWS, Kindle, Prime, Amazon Go. The company’s most successful innovations were born not from slick presentations but from rigorous written thinking.

The question is why. What makes a written document better than slides for innovation? And more importantly, how does the six pager method actually work?

The Tyranny of the Bullet Point

Here’s what happens when you put an innovation idea into PowerPoint. You open a blank slide. You type a title. Then you face the little text box, and something in your brain shifts. The software asks you to summarize. To condense. To fit your thought into a bullet point that won’t overwhelm the slide.

So you do.

And in that moment, you’ve already lost something. The nuance. The complication. The very thing that made your idea interesting in the first place.

PowerPoint is optimized for simplicity. Innovation is optimized for complexity that eventually becomes simple. These are not the same thing.

Think about how scientific papers work. They don’t start with the conclusion. They walk you through the reasoning. The methodology. The data. The alternative explanations they considered and rejected. By the time you reach the conclusion, you’ve done the thinking alongside the author. You understand not just what they concluded, but why.

A slide deck gives you the conclusion and asks you to trust the presenter. This might work for reporting results. It fails catastrophically for developing new ideas.

How the Six Pager Actually Works

The Amazon six pager has specific rules, and those rules are not arbitrary. They’re designed to force a particular kind of thinking.

First, the length. Six pages maximum. Not five, not seven. This is long enough to develop a complete argument but short enough that people will actually read it. The constraint forces you to think about what matters. You can’t include everything. You have to make choices about what’s essential.

Second, the format. It must be written in complete sentences, organized in paragraphs, with a narrative structure. No bullet points. No charts standing alone without explanation. No executive summary that lets people skip the thinking.

The typical structure follows a logical progression. You start with the context and the problem you’re trying to solve. Not a bullet list of pain points, but a real explanation of why this problem matters and why it matters now. You describe the customer and their needs in detail. Who are they? What are they trying to do? Where are current solutions failing them?

Then you present your proposed solution. But here’s the key: you have to explain it well enough that someone who has never heard of your idea can understand it completely. This is harder than it sounds. When an idea lives in your head, you understand all the connections. When you have to write it for someone else, you discover all the gaps in your own thinking.

You must address how the solution works operationally. What does the customer experience look like? What does the internal process look like? What resources are required? This is where most ideas fall apart. They sound good in theory but become obviously impractical when you have to describe the actual mechanics.

Next comes the hard part: you must articulate the benefits and explain why this idea is better than alternatives. Not just “this is good” but “this is better than the obvious other options, and here’s why.” You have to engage with objections before anyone raises them. What are the risks? What could go wrong? What assumptions are you making that might not hold?

Finally, you need to address feasibility and resources. What will this cost? How long will it take? What capabilities do we need that we don’t currently have?

The document is written from the customer’s perspective whenever possible. Amazon calls this “working backwards.” You start with the customer need and work backwards to the solution, not the other way around. This prevents you from falling in love with a technology or approach and then trying to find a problem it solves.

Some teams at Amazon add a FAQ section at the end, anticipating questions and objections. Others use appendices for detailed data that supports the narrative but would bog down the main text. The key is that everything must serve the goal of clear thinking.

The Silent Reading Revolution

Here’s where the method gets really interesting. After someone has spent days or weeks writing this document, you might think the meeting would start with them presenting it. Walking people through the thinking. Highlighting the key points.

Amazon does the opposite.

The meeting starts with silence. Everyone, including the author, sits down and reads the document. For about thirty minutes, nobody talks. You just read. The author doesn’t present. The executives don’t skim. Everyone engages with the same text at the same time.

This feels weird at first. Unproductive. Like you’re wasting the most expensive time in the company: the time when senior leaders are all in one room.

But the silent reading does something PowerPoint can never do. It creates genuine shared context.

When someone presents slides, you’re not thinking about their idea. You’re thinking about what question you’re going to ask. What critique you’re going to make. How you’re going to sound smart when it’s your turn to talk. You’re performing attention instead of paying it.

You can’t interrupt a document. You can’t skip ahead to look smart. You have to actually engage with the thinking on the page. Your brain processes the information in the order the author intended. You see the full argument before you start poking holes in it.

The silent reading also equalizes the room. In a presentation, the charismatic person has an advantage. The person who speaks well, who commands attention, who knows how to work a room. These skills have nothing to do with whether their idea is good.

When everyone reads silently, charisma doesn’t matter. The idea has to stand on its own. The quiet engineer with the brilliant insight has the same platform as the smooth talking executive. The quality of thinking becomes visible in a way it never is during a performance.

Why Writing Forces Better Thinking

The six pager works because writing is not just communication. Writing is thinking made visible.

When you write, you discover what you actually believe. You find the contradictions in your reasoning. You notice the assumptions you didn’t know you were making. The act of putting words on a page forces your fuzzy intuitions into concrete claims.

In a slide deck, you can write “Improve customer experience” on a bullet point and move on. In a narrative, you have to explain what that means. Improve it how? For which customers? Compared to what? Measured by what metric? The sentence structure itself demands specificity.

This is why you can’t hide weak thinking in a six pager the way you can in slides. In PowerPoint, you might have a slide that says “Market Opportunity” with a big number on it. That number creates an impression of rigor. But where did it come from? What assumptions went into it? What does it actually mean?

In a written document, you have to connect the dots. “We estimate the market opportunity at $5 billion because we’re targeting small businesses with 10 to 50 employees, there are approximately 2 million such businesses in the US, our research suggests 40% of them face this problem, and our solution would cost them roughly $6,000 per year.”

Now you’ve made your reasoning visible. Someone can challenge your assumptions. They might say “I think the real percentage is closer to 20%, not 40%.” And you can have a real conversation about whether your estimate makes sense.

The six pager also forces you to deal with complexity honestly. Some ideas are genuinely complex. They require you to understand multiple interconnected concepts. Slide decks handle this poorly because they’re linear. Point A, point B, point C. But what if point A only makes sense after you understand point C?

In a narrative, you can say “I need to explain the distribution model first, even though it won’t make complete sense until I describe the product architecture in the next section.” You can create a web of understanding instead of a sequence of claims.

The format also makes you confront what you don’t know. In slides, you can skip over uncertainties. In prose, gaps in your knowledge create gaps in your sentences. You write “This will require approximately…” and you stop. How long? You don’t know. Now you have to either figure it out or write “This will require additional analysis to determine the timeline, but initial estimates suggest…” You’ve made your uncertainty explicit instead of hiding it.

The Discussion That Follows

After the silent reading ends, the real meeting begins. And this meeting is different from a typical PowerPoint review in crucial ways.

First, everyone has actually read the proposal. They’ve had time to think. They can ask substantive questions instead of clarifying questions. “What did you mean by…” has already been answered by the document.

Second, because everyone read the same thing at the same time, they’re reacting to the actual idea, not to their interpretation of a presentation. There’s no “I thought you said…” The document is right there. Everyone can reference it.

Third, the author isn’t defensive in the same way. When someone challenges a presentation, they’re challenging your performance. When someone challenges a document, they’re engaging with your reasoning. This is a subtle shift, but it changes the emotional tone completely.

The meeting becomes about improving the idea instead of defending it. “I noticed you said the implementation would take six months. Have you considered that the compliance review alone typically takes three months?” This isn’t an attack. It’s a contribution. The author can say “You’re right, I need to revise that timeline.”

At Amazon, these meetings often result in the author going back to revise the document and scheduling another meeting. This sounds inefficient until you realize that the alternative is approving a half baked idea and discovering the problems six months into execution.

The six pager method also has an interesting effect on organizational culture. It rewards clear thinking over smooth talking. It values depth over flash. People who are good at writing coherent arguments get their ideas heard. People who are just good at presenting eventually get found out.

This doesn’t mean presentation skills don’t matter at Amazon. They do. But they matter in different contexts. When you’re trying to convince customers or investors, present away. When you’re trying to develop internal innovations, write.

The Hidden Benefit: A Record of Thinking

Here’s something most people miss about the six pager approach. After the meeting, you have a document. A permanent record of what was proposed and why.

Six months later, when the project isn’t working, you can go back and read what you originally thought. You can see which assumptions held and which didn’t. You can learn from the gap between what you predicted and what actually happened.

With slides, this is much harder. The slides capture conclusions but not reasoning. “Expand to three new markets” tells you what was decided, but not why those markets, not what the team believed about competitive dynamics or customer needs.

The six pager creates institutional memory. New team members can read old proposals and understand how decisions were made. People can see patterns in what works and what doesn’t.

This is particularly valuable for innovation because innovation is inherently about learning. You try things. Some work, some don’t. The question is whether you extract the lessons.

Amazon can look back at proposals for features that succeeded and proposals for features that failed. They can ask: what was different in the reasoning? Were there warning signs in the original document that people missed? What kinds of assumptions tend to be wrong?

You can’t do this kind of meta analysis with PowerPoint decks. The thinking isn’t captured in a form that allows for serious review.

The False Clarity of Charts and Graphs

Slide decks love data visualization. A good chart can make an argument feel scientific, rigorous, backed by evidence. And sometimes it is.

But often, the chart is doing something more insidious. It’s creating the appearance of clarity where none exists.

Here’s a test. Next time you see a chart in an innovation presentation, ask yourself what happens if you remove it. Does the argument fall apart? Or does it just become obvious that the argument was never that strong to begin with?

Charts in slide decks often function as rhetorical decoration. They make the presentation look serious. They give people something to focus on besides the logical gaps. They suggest that someone did analysis, even if that analysis doesn’t actually support the conclusion being drawn.

In a written document, you can’t get away with this as easily. Because you’re writing in sentences, you have to explain what the data means. You have to connect it to your argument. You have to spell out the logical steps between the data point and the conclusion.

If those steps don’t exist, the reader notices. The sentence structure itself exposes the gap.

This is why good writing is hard. It makes fuzzy thinking visible.

The Paradox of Preparation

Here’s something strange about the Amazon approach. Writing a six page narrative takes longer than making thirty slides. Much longer. You might spend days on a document you could bang out as a slide deck in an afternoon.

This seems inefficient. Until you realize that the time you save making slides, you lose in the meeting. And then in the follow up meetings. And then in the pivot meetings when the project fails because nobody really understood it in the first place.

The six pager frontloads the thinking. You work hard before the meeting so the meeting can actually be productive. You find the problems with your idea while you’re writing, not six months into execution.

There’s a parallel here with how doctors are trained. Medical students learn to write patient notes in a specific format. Chief complaint, history of present illness, past medical history, physical exam, assessment, plan. Always in that order.

Why? Because the structure forces you to think systematically. You can’t jump to a diagnosis without documenting your reasoning. The format makes you confront what you don’t know.

Innovation documents should work the same way. They should have a structure that forces comprehensive thinking. Not because structure is inherently good, but because it prevents you from fooling yourself.

The Meeting After the Meeting

You know what happens after a bad PowerPoint presentation. People file out of the room. In the hallway, the real conversation starts. This is where people say what they actually think. This is where the idea actually gets evaluated.

The meeting after the meeting is where innovation goes to die.

Because by the time you have this honest conversation, the person who proposed the idea isn’t there. They can’t defend it. They can’t clarify. They can’t adjust based on the feedback. So the idea gets killed by people who don’t fully understand it, based on concerns that might have been addressable.

Written documents with shared reading time collapse the meeting after the meeting back into the actual meeting. Everyone is reacting to the same information. The conversation happens while the author is present. Misunderstandings get corrected in real time.

This is more uncomfortable. It’s also more honest.

The Innovation Theater Problem

Most companies don’t want innovation. They want innovation theater. They want the appearance of being innovative without the discomfort of actual change.

PowerPoint is perfect for this. You can have innovation meetings. You can review innovation proposals. You can fund innovation projects. And none of it requires anyone to actually think differently or take real risks.

The slide deck allows everyone to maintain plausible deniability. The idea wasn’t really explained. The problems weren’t really visible. Everyone can claim they were supportive while the project was just obviously doomed from the start.

A well written document removes this escape hatch. The thinking is on the page. The assumptions are explicit. The risks are acknowledged. If you approve it, you’re actually committing to something.

This is why most companies will never adopt the Amazon approach, even though they claim to want innovation. They don’t want the accountability that comes with clear thinking.

What Gets Lost in Translation

There’s a specific kind of idea that dies in PowerPoint. The complex idea. The idea that requires you to hold multiple concepts in your head simultaneously. The idea that looks wrong until you understand the full picture.

Slide decks are linear. One point after another. But some ideas aren’t linear. They’re networked. Point A only makes sense in light of point C, which you won’t get to for another six slides.

By the time you reach point C, everyone has already decided point A is stupid.

Written narratives can handle this complexity. You can reference back. You can say “remember what I mentioned about the distribution model earlier, this is where it becomes relevant.” You can build an argument that loops back on itself and creates understanding through layers.

This is how actual innovation thinking works. It’s not a straight line from problem to solution. It’s a web of insights that reinforce each other until a picture emerges.

PowerPoint flattens this web into a sequence. And in doing so, it kills the idea.

The Cognitive Load Problem

Here’s what your brain is doing during a PowerPoint presentation. It’s reading the slide. It’s listening to the presenter. It’s trying to reconcile when those two things don’t match. It’s tracking what question you want to ask. It’s monitoring how much time is left. It’s wondering if everyone else is as confused as you are.

This is too much. Your working memory, the part of your brain that handles active thinking, can only manage a few things at once. When you overload it, you stop actually processing information. You go into a kind of survival mode where you’re just trying to keep up.

Silent reading removes most of this load. You’re just reading. Your brain can focus on understanding rather than juggling.

This matters more for innovation than for other types of meetings because innovation ideas are inherently unfamiliar. You’re asking people to consider something new. Something that challenges their existing mental models. This requires cognitive space.

PowerPoint fills that space with performance and logistics. Reading creates space for actual thinking.

Starting Your Own Six Pager Practice

You probably can’t ban PowerPoint from your organization tomorrow. The inertia is too strong. The habit is too ingrained. People will revolt.

But you can start small. You can adopt the six pager method for your own team’s innovation decisions. Here’s how.

Start by explaining the why. Don’t just announce “we’re doing six pagers now.” Explain what you’re trying to achieve. Better thinking. More honest conversations. Ideas that survive contact with reality. People are more likely to embrace a new approach when they understand the reasoning behind it.

Set clear expectations for the document format. Six pages maximum, written in narrative form, complete sentences and paragraphs. Include the problem, the proposed solution, how it works, why it’s better than alternatives, risks and assumptions, and resource requirements. Give people a template if that helps, but don’t be too prescriptive. Part of the value comes from wrestling with how to structure your own argument.

The first few documents will be rough. People aren’t used to writing this way. They’ll want to include bullet points. They’ll struggle with the page limit. They’ll write in the passive voice and hide behind vague language. This is normal. Give feedback that helps them get better.

Schedule time for silent reading and protect it fiercely. The first time you do this, people will feel awkward. Someone will try to break the silence. Someone will apologize for reading slowly. Don’t let the awkwardness derail the process. Sit there and read. Let the silence do its work.

After reading, start the discussion by asking the author what questions they’re most worried about. This sets a tone of collaborative problem solving instead of interrogation. Then open it up for everyone to engage with the ideas in the document.

Revise and iterate. The first version of a six pager is rarely the final version. Expect to go through multiple drafts. Expect to have meetings where the conclusion is “this needs more work.” That’s not failure. That’s the process working as intended.

Track your results. After you’ve used the six pager method for a few innovation decisions, compare the outcomes to decisions made the old way. Are the projects that went through written analysis more successful? Are they better scoped? Do they encounter fewer unexpected problems? Let the results speak for themselves.

The six pager method isn’t magic. It won’t make bad ideas good. But it will make bad ideas visible before you waste six months executing them. And it will make good ideas better by forcing you to think them through completely.

The Deeper Pattern

The six pager is part of a broader pattern that high performing organizations share. They make thinking visible. They create processes that expose fuzzy reasoning and reward clarity.

At Pixar, they have “Braintrust” meetings where directors show rough cuts of films and get brutally honest feedback. The feedback works because everyone understands they’re critiquing the work, not the person. The rough cut is like a six pager. It’s the idea in a form that can be examined and improved.

In software development, code reviews serve a similar function. You can’t merge code until someone else has read it and understood it. This catches bugs, sure. But more importantly, it catches unclear thinking. If your code is hard to understand, that’s a sign you haven’t thought through the problem properly.

The military uses after action reviews. What was supposed to happen? What actually happened? Why was there a difference? What should we do differently next time? They write these down. They study them. They learn from them.

These practices share a common thread. They externalize thinking so it can be examined. They create feedback loops that reward clarity and expose gaps. They build organizational capabilities over time instead of relying on individual heroics.

The six pager is Amazon’s version of this pattern. It’s their answer to the question: how do we make sure we’re making innovation decisions based on sound reasoning rather than persuasive presentations?

The Uncomfortable Truth

Innovation is hard. Not because coming up with ideas is hard. Ideas are easy. Everyone has ideas. Innovation is hard because developing ideas into something real requires rigorous thinking, and rigorous thinking is uncomfortable.

PowerPoint makes it comfortable. It lets you pretend you’ve thought things through when you haven’t. It lets you perform innovation instead of doing it.

The six pager makes it uncomfortable. It forces you to think. To write. To expose your reasoning to scrutiny.

Most ideas don’t survive this scrutiny. And that’s exactly why it works. Because the few ideas that do survive are the ones worth pursuing.

Your innovation graveyard is full of slide decks. Maybe it’s time to try something else.