Table of Contents

In 1962, sociologist Everett Rogers published a book that would become one of those rare academic works that actually matters beyond university walls. His Diffusion of Innovation theory explained how new ideas spread through societies, and it’s been applied to everything from farming techniques in developing countries to electric vehicle adoption in Silicon Valley. The framework is deceptively simple, which is probably why it has endured for over six decades and remains relevant in our digital age.

But here’s what makes it interesting in our current moment: the theory was developed by studying how Iowa farmers decided whether to plant hybrid corn. Today, we’re using the same framework to understand how people adopt artificial intelligence tools, cryptocurrency, and plant-based meat alternatives. The fact that a model built on agricultural decisions still helps us make sense of technology adoption six decades later tells us something important about human nature. We’re not as different from those farmers as we might think.

The Basic Architecture of Diffusion of Innovation

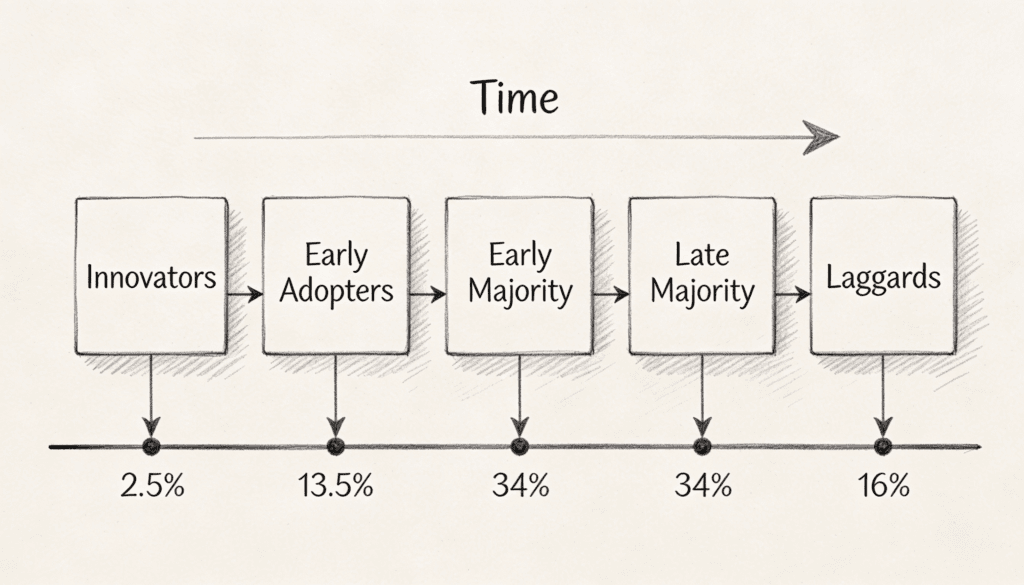

Rogers divided adopters of any innovation into five categories based on when they embrace something new. Think of it as a bell curve that describes human behavior toward change.

Innovators make up the first 2.5% of adopters. These are the people camping outside Apple stores or installing beta versions of software that will probably crash their computers. They have a high tolerance for risk and often have the financial resources to absorb failures. Innovators are cosmopolitan in their outlook, maintaining connections outside their immediate social circle. They’re willing to cope with uncertainty because the possibility of being first matters more than the guarantee of stability.

Early adopters are the next 13.5%. This group is crucial because they serve as opinion leaders within their communities. Unlike innovators, who are sometimes dismissed as eccentrics, early adopters are respected members of their social systems. When they endorse an innovation, others pay attention. They’re selective about what they adopt, which paradoxically gives their choices more weight. Think of them as the people whose restaurant recommendations you actually follow.

Early majority accounts for 34% of adopters. These people are deliberate. They want to see evidence that something works before committing. They interact frequently with peers and seldom hold leadership positions, but they’re essential for making an innovation mainstream. Without this group, even the most promising innovations remain niche curiosities.

Late majority is another 34%. They approach innovation with skepticism and caution. Economic necessity or social pressure often drives their adoption more than enthusiasm. They want most of the uncertainty removed before they’ll try something new. By the time they adopt, the innovation is usually well established and the bugs have been worked out.

Laggards make up the final 16%. They’re oriented toward the past and suspicious of change. Their reference point is what worked before, and they interact primarily with others who share their traditional values. They adopt innovations only when they have no choice or when the innovation has become the new tradition.

The labels can sound judgmental, but that misses the point. A person might be an innovator for kitchen gadgets but a laggard for social media platforms. These categories describe behavior toward specific innovations, not fixed personality types.

The Five Factors That Determine Speed

Not all innovations spread at the same rate. Rogers identified five characteristics that determine how quickly something gets adopted.

Relative advantage is straightforward. If something is clearly better than what it replaces, people adopt it faster. But “better” is subjective. Email had an obvious advantage over postal mail for speed, but some people still prefer physical letters for certain communications. The advantage has to be perceived by potential adopters, not just measured by objective metrics.

Compatibility with existing values and practices matters enormously. This is why electric cars struggled for decades despite clear environmental benefits. They challenged assumptions about vehicle range, refueling infrastructure, and even what a “real” car sounds like. Innovations that require people to rethink their entire framework face an uphill battle.

Complexity acts as a barrier. If something is difficult to understand or use, adoption slows. This is where we see interesting conflicts in technology development. Engineers often optimize for capability while users optimize for simplicity. The most successful innovations find ways to hide complexity behind simple interfaces. The iPhone succeeded partly because it made sophisticated technology feel intuitive.

Trialability accelerates adoption. When people can experiment with something on a small scale before committing, they’re more willing to try it. This is why software companies offer free trials and car manufacturers encourage test drives. The ability to reverse course reduces perceived risk.

Observability means others can see you using the innovation. Visible innovations spread faster because they generate conversations and normalize the behavior. This is why fashion trends move quickly but changes in personal financial management spread slowly. Nobody sees your new budgeting system, but everyone notices your new shoes.

Where the Model Gets Really Interesting

The framework reveals patterns that feel counterintuitive until you think them through carefully.

First, the most important adopters for an innovation’s success are often not the earliest ones. Innovators and early adopters get attention, but the early majority determines whether something crosses into mainstream acceptance. This group moves more slowly and deliberately, which frustrates companies seeking explosive growth. But their caution serves a function. They filter out innovations that look promising but lack substance.

Second, communication between different adopter categories is surprisingly difficult. Innovators speak a different language than the early majority. They emphasize different benefits and tolerate different tradeoffs. This is why successful companies often need different marketing strategies as they move through the adoption curve. The message that excites innovators can alienate the mainstream.

Third, innovations sometimes fail not because they’re inferior but because they spread too quickly to the wrong people. When an innovation jumps straight from innovators to the late majority, skipping the crucial opinion leaders in between, adoption often collapses. The late majority adopted something without proper social proof, and they retreat when problems emerge. This happened with various cryptocurrency projects that went viral among retail investors before establishing credibility with more knowledgeable adopters.

The Social System Matters More Than the Innovation

Here’s something Rogers emphasized that often gets overlooked: diffusion happens within social systems, and those systems shape outcomes as much as the innovation itself.

Some societies are more innovation-friendly than others. This isn’t about intelligence or resources. It’s about norms, values, and structures. A community might reject an objectively superior farming technique because adopting it would disrupt existing power relationships or violate cultural practices. The innovation itself is almost beside the point.

This has implications for how we think about technology adoption today. We often assume that better products naturally win, but that’s not how it works. Products win when they align with social structures, when they’re championed by the right people, and when they’re introduced in ways that respect existing relationships.

Consider how social media platforms spread. Facebook didn’t succeed because it was technically superior to MySpace. It spread through college networks, leveraging existing social structures and the opinions of influential students on each campus. The technology mattered, but the social strategy mattered more.

The Reinvention Problem

Rogers documented something he called reinvention: the degree to which people modify an innovation during adoption. This happens more than innovators usually expect or want.

A company releases a product designed for one purpose, and users find entirely different applications. Twitter was supposed to be a status update service. Users turned it into a news platform, a customer service channel, and a venue for social movements. The original vision became almost irrelevant.

Reinvention can be beneficial or problematic. It shows that users have agency and creativity. But it also means that the innovation’s ultimate impact is partly beyond any creator’s control. This troubles people who want to predict outcomes precisely. The messiness of actual adoption doesn’t match the clean logic of business plans.

Speed Is Not Always Good

Our current culture valorizes rapid adoption. Companies compete to achieve viral growth and minimal time to mainstream acceptance. But Rogers found that the speed of diffusion isn’t necessarily correlated with positive outcomes.

Some innovations spread quickly and later prove harmful. Others spread slowly but create lasting value. The rate of adoption is morally neutral. What matters is whether the innovation actually improves things for the people who adopt it.

Fast diffusion can even be destructive. When a practice spreads before we understand its consequences, entire populations can make mistakes simultaneously. The widespread adoption of certain agricultural chemicals followed this pattern. Farmers adopted them rapidly because of clear short term benefits, and the long term environmental costs only became apparent after the practices were entrenched.

This creates a tension. Innovators want rapid growth. But society sometimes benefits from slower, more thoughtful adoption that allows for learning and adjustment. There’s no easy resolution to this tension, which is why debates about technology regulation remain contentious.

What the Framework Misses

No model is perfect, and Rogers himself acknowledged limitations.

The categories are descriptive, not prescriptive. Knowing someone is an innovator doesn’t tell you which innovations they’ll embrace. The framework describes patterns but doesn’t predict individual behavior with precision.

The model assumes innovations are beneficial, or at least neutral. But some innovations are actively harmful. The theory describes how things spread without always asking whether they should spread. Misinformation diffuses through social systems following these same patterns, which is uncomfortable to acknowledge.

The framework was developed in a slower era. Today, digital networks allow innovations to spread globally in days rather than years or decades. The compressed timeline changes dynamics in ways the original theory doesn’t fully capture. Early adopters have less time to evaluate and refine innovations before they reach the mainstream.

Practical Applications Today

Despite these limitations, the framework remains useful for anyone trying to understand or influence how new ideas spread.

If you’re introducing an innovation, focus first on identifying and convincing opinion leaders in your target communities. These early adopters provide social proof that the mainstream needs. Trying to skip this step and appeal directly to the early majority usually backfires.

Make your innovation easy to try without full commitment. Lower the barriers to experimentation. Let people test your idea in small, reversible ways before asking for major changes to their behavior or beliefs.

Show, don’t just tell. Make the benefits observable. People trust what they can see working for others more than they trust what you claim in marketing materials.

Respect compatibility with existing practices. Innovations that require people to change too much at once face enormous resistance. Find ways to fit into current workflows and habits rather than demanding wholesale transformation.

Be patient with the early majority. They move more slowly than innovators, but their caution isn’t irrational. They’re managing different risks and operating under different constraints. Understanding their perspective is essential for mainstream success.

The Enduring Insight

What makes the diffusion framework timeless is its focus on people rather than technology. The specific innovations change rapidly. Human social behavior changes much more slowly.

We still adopt innovations through social processes, influenced by people we respect, constrained by existing practices, and driven by a complex mix of rational calculation and social pressure. The medium of communication has changed from face to face conversations in farming communities to social media networks spanning the globe. But the fundamental dynamics remain recognizable.

This is either reassuring or depressing, depending on your perspective. It means we can apply lessons learned from studying hybrid corn adoption to understanding artificial intelligence adoption. But it also means we’re probably going to keep making similar mistakes, just with fancier tools.

The farmers in Iowa who hesitated before planting hybrid corn were using the same mental processes as someone today deciding whether to try a new app or adopt a new business practice. They were watching what others did, consulting people they trusted, weighing risks and benefits, and trying to predict consequences. Understanding this continuity helps us navigate change more wisely.

In a culture obsessed with disruption and novelty, there’s something almost radical about recognizing how much stays the same. The tools change but the humans using them remain fundamentally human. That simple insight might be the most valuable thing Rogers gave us.