Table of Contents

Steve Jobs never talked about design thinking. He talked about taste.

This matters more than you might expect. While the rest of Silicon Valley was busy workshopping their way through sticky notes and empathy maps, Jobs was building products that people lined up around the block to buy. The irony is that everyone now studies his approach as the ultimate example of design thinking, even though he would have rolled his eyes at the term.

The gap between what Jobs actually did and what we think he did reveals something important about how innovation really works. We’ve turned his method into a process, his intuition into a framework, his taste into a checklist. In doing so, we’ve missed the point entirely.

The Tyranny of the Process

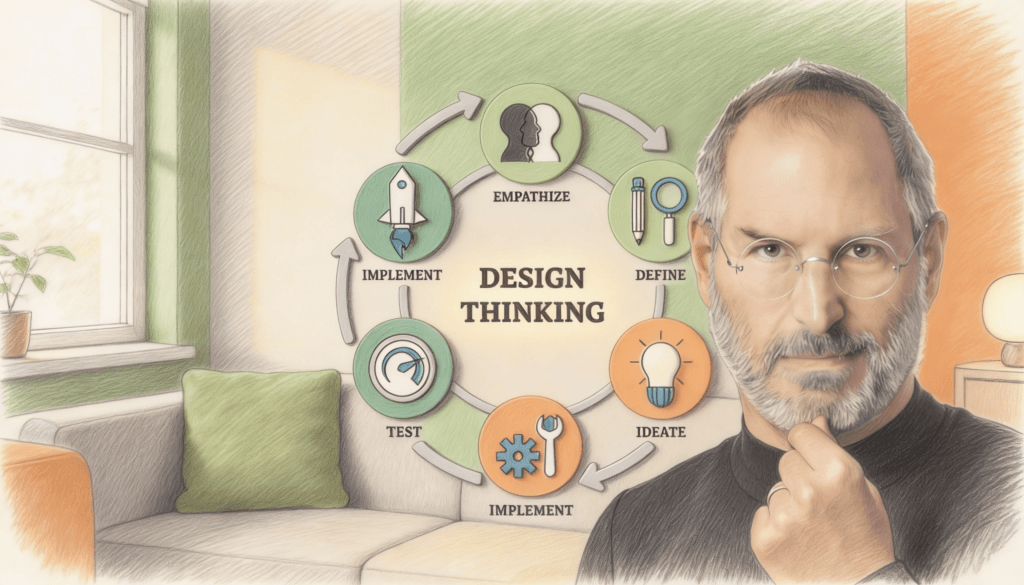

Design thinking as we know it today emerged from IDEO and Stanford in the early 2000s. It gave us a neat five step process: empathize, define, ideate, prototype, test. It promised that anyone could innovate if they just followed the steps. It made innovation democratic, accessible, teachable.

Jobs would have hated it.

Not because the steps are wrong. They’re not. But because treating them as a recipe misses what actually matters. Jobs understood something that gets lost when you turn creativity into a process: great design comes from a point of view, not from a method.

Think about the first iPhone. Everyone focuses on how it removed the keyboard, introduced multi-touch, combined three devices into one. These were the visible innovations. But the deeper innovation was philosophical. Jobs believed that people didn’t want more features. They wanted things that just worked. This wasn’t something he discovered through user research. It was a thesis about human nature that he held before he talked to a single customer.

The design thinking process would have you start with empathy, with understanding your user. Jobs started with conviction. He had a vision of what people should want, even if they didn’t know it yet. This sounds arrogant, and it was. But it was also effective in a way that pure empathy can never be.

The Problem With Asking People What They Want

Henry Ford supposedly said that if he’d asked people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses. Whether he actually said this or not, the sentiment captures something true. People are very good at telling you about their current problems. They’re terrible at imagining solutions that don’t exist yet.

Jobs grasped this at a bone deep level. When asked how much customer research went into the iPad, he said none. “It’s not the customers’ job to know what they want,” he explained. This sounds like the opposite of design thinking, which places the user at the center of everything.

But here’s the subtle part: Jobs was intensely interested in people. He just wasn’t interested in what they said they wanted. He was interested in what frustrated them, what they struggled with, what they settled for. He watched how people actually used technology, not how they claimed to use it. He paid attention to the gap between what people did and what they could do.

This is a different kind of empathy. It’s not about making people feel heard or validated. It’s about understanding them better than they understand themselves. It’s a more aggressive form of caring, one that’s willing to tell people they’re wrong about their own needs.

Taste Cannot Be Democratized

When Jobs returned to Apple in 1997, the company was making dozens of products. None of them were particularly good. One of his first moves was to cut the product line down to four devices. He didn’t run focus groups to decide which products to keep. He simply applied his own taste.

This is where design thinking runs into trouble. The methodology is built on the idea that good design emerges from a collaborative, iterative process. And it can. But the very best design usually emerges from a single, coherent vision. You can’t get that from a committee, no matter how well facilitated.

Jobs believed in taste the way a wine expert believes in terroir. It’s something you develop over years of exposure, something you can refine but not fabricate. He filled his company with people who had it and fired people who didn’t. This created a culture where aesthetic judgment was taken as seriously as technical skill.

The modern corporation struggles with this. Taste is subjective, hard to measure, impossible to put in a performance review. Process is objective, measurable, defensible. If something goes wrong, you can point to the process and say “we followed it.” You can’t point to taste and say “we had it.”

This is why most companies end up with products that are competent but not compelling. They followed the process. They checked the boxes. They did everything right. But somewhere along the way, they forgot to have a point of view.

The Aesthetics of Simplicity

Jobs was obsessed with simplicity, but not the kind of simplicity that design thinking usually produces. Design thinking simplicity tends to be about ease of use, about removing friction, about making things intuitive. These are good goals. But they produce a certain blandness, a lowest common denominator quality.

Jobs’s simplicity was different. It was opinionated. The first iPod had no screen that showed you all your songs at once. The iPhone had no stylus, no keyboard, no removable battery. The MacBook Air had no CD drive, no Ethernet port, almost no ports at all. Each of these decisions made the products harder to use for certain tasks. They were simplifications that subtracted capability in service of a vision.

This is counterintuitive. We tend to think of good design as additive, as giving people more options, more control, more ways to use something. Jobs understood that constraints create clarity. By taking things away, he forced both his team and his users to focus on what actually mattered.

The design thinking process tends to add, not subtract. You gather insights, you generate ideas, you layer on features to address every use case you discovered. Jobs worked in reverse. He started with everything and carved away until only the essential remained. Like a sculptor, he believed the form was already there. His job was just to reveal it.

The Follow Through That Everyone Forgets

Design thinking workshops are exciting. You generate ideas, you sketch prototypes, you feel creative and energized. Then you go back to your desk and nothing happens. The ideas sit in a slide deck somewhere. The prototypes gather dust. The energy dissipates.

Jobs’s genius wasn’t just having ideas. It was in the relentless, often brutal follow through. He attended design meetings about the curves of the iPhone’s corners. He obsessed over the box the product came in. He made his team redo things dozens of times until they were right. Not good. Right.

This part isn’t fun. It doesn’t fit on a workshop agenda. It’s the grinding, unglamorous work of actually making something great. Design thinking gives you the exciting front end of innovation. It’s silent about the years of refinement that follow.

There’s a reason for this. Process can take you from nothing to something. It can’t take you from good to great. That final distance requires something else: obsession, perfectionism, an almost pathological inability to settle. These aren’t qualities you can teach in a workshop. They’re barely qualities you’d want to teach at all. They make you difficult to work with. They make you miss deadlines. They make you expensive.

But they also make you excellent.

Integration Over Isolation

Most companies organize around functions. Engineering sits over here, design sits over there, marketing sits somewhere else. They coordinate through meetings and handoffs. Design thinking tries to bridge this gap by bringing everyone together for workshops. It’s a start, but it’s not enough.

Jobs built Apple around integration. Hardware engineers worked next to software engineers. Designers sat with product managers. The retail team helped shape product development. This wasn’t collaboration in the modern sense. It was fusion. You couldn’t tell where one discipline ended and another began.

This created products where everything fit together. The hardware complemented the software. The packaging extended the product experience. The retail stores reflected the design philosophy. Even the marketing materials felt like they came from the same brain as the product itself.

Design thinking talks about cross functional teams. Jobs created something deeper: a shared aesthetic language that everyone in the company spoke fluently. An engineer at Apple had to understand design. A designer had to understand engineering. This wasn’t about respecting each other’s domains. It was about erasing the boundaries between domains entirely.

You see this in the products. The iPhone’s rounded corners match the rounded corners of its icons. The physical click of the home button was tuned to feel satisfying. The weight distribution was calculated to feel substantial but not heavy. Every detail was considered not in isolation but as part of a complete experience.

Most products feel like they were assembled from parts. Apple products feel like they grew organically into their final form. That’s not an accident. It’s the result of an integrated design process that most design thinking workshops can’t replicate because they’re still fundamentally about coordination, not integration.

The Courage to Say No

Jobs was famous for saying no. He said no to good ideas, profitable ideas, ideas his team had spent months developing. He said no more than he said yes. This is the part of his approach that gets talked about least, probably because it’s the hardest to do.

Design thinking encourages divergent thinking. You want lots of ideas. You want to explore possibilities. You don’t want to shut things down too early. This is useful in the early stages. But at some point, you have to converge. You have to choose. More importantly, you have to choose what not to do.

Most organizations are bad at this. Saying no feels negative, restrictive, political. It’s easier to say yes and figure it out later. So products accumulate features, companies accumulate products, strategies accumulate initiatives. Everything is a priority, which means nothing is.

Jobs made saying no a core competency. When he looked at a product, he wasn’t thinking about what else it could do. He was thinking about what it shouldn’t do. This created products with clear identities, products that were great at one thing instead of mediocre at many things.

The courage to say no requires something design thinking can’t give you: conviction. You have to believe strongly enough in your vision that you’re willing to disappoint people. You have to trust your taste more than you trust consensus. You have to be okay with being wrong sometimes because that’s the price of being right when it matters.

The Unspoken Foundation

Underneath all of Jobs’s design decisions was something rarely discussed: he was building for himself. He wanted a phone that he would want to use. He wanted a computer that he would want to own. He wanted stores that he would want to shop in. His taste wasn’t some abstract quality. It was deeply personal.

This is the secret that design thinking can’t package into a process. Jobs wasn’t designing for a persona or a target demographic. He was designing for a very specific person who happened to be himself. He trusted that if he made something he loved, other people would love it too.

This sounds narcissistic. Maybe it was. But it was also honest in a way that market research can never be. When you design for yourself, you can’t hide behind data or user feedback. You have to take full responsibility for your choices. Your taste is on the line.

Most companies can’t do this. They don’t trust any individual’s taste enough to let it guide major decisions. They need validation, buy in, proof. Design thinking gives them that. It provides a rational framework for what is ultimately an irrational act: creating something new.

But the truly innovative companies, the ones that change industries and create new categories, usually have someone at the top whose taste is so strong, so coherent, so specific that it becomes a competitive advantage. That person might be wrong sometimes. They’ll definitely be difficult to work with. But they’ll also create things that feel inevitable in retrospect, things that make you wonder why nobody thought of it before.

What This Means For You

So where does this leave design thinking? Is it useless?

No. It’s a valuable tool, especially for organizations that have no design culture at all. It creates a shared language. It encourages experimentation. It puts the user back into the conversation. These are good things.

But it’s not sufficient for greatness. For that, you need something else. You need taste, conviction, vision. You need someone willing to impose their point of view on the world. You need the courage to say no. You need the patience to refine endlessly. You need integration, not coordination.

Design thinking can get you into the game. It can’t win the game for you.

The real lesson from Jobs isn’t about following a process or skipping a process. It’s about having something to say. He didn’t just make products. He made arguments about how technology should work, how people should interact with computers, what role design should play in our lives. His products were answers to questions most people didn’t know they were asking.

You probably can’t be Steve Jobs. Most people can’t. But you can steal his actual method, not the sanitized version. Start with a point of view. Build taste. Say no more than yes. Integrate everything. Refine endlessly. Care more about being right than being liked.

Design thinking will give you a map. Jobs knew you also need a destination. One that you believe in enough to be difficult about, wrong about, obsessive about. The map helps you avoid getting lost. The destination gives you a reason to start walking.

That’s the difference between process and vision. Process gets you moving. Vision tells you where to go. Jobs had both, but he never confused which one mattered more.