Table of Contents

The chair you’re sitting in was probably designed with your spine in mind. The keyboard under your fingers has keys positioned to minimize wrist strain. The screen you’re staring at sits at an angle meant to protect your neck. We’ve spent decades perfecting the physical workspace, sculpting it around the human body like clay around a skeleton.

But nobody designed the spreadsheet for how your brain actually processes information. Nobody engineered the notification system around your attention span’s natural rhythms. And that enterprise software you use every day? It was built for computers first, humans second.

Welcome to 2026, where the most valuable innovation isn’t happening in AI models or quantum computers. It’s happening in the space between how technology works and how humans think. We call it cognitive ergonomics, and it’s about to become the most lucrative form of adjacent innovation in the next decade.

The Invisible Overhead We’ve Been Ignoring

Think about how much time you spend every day translating between what you want to do and what the tool requires you to do. You want to find that email from three weeks ago about the budget meeting. The tool wants you to remember if it came before or after that other email, whether the sender used “budget” or “financial planning” in the subject line, and if you filed it in the Projects folder or the Q1 folder or just left it in your inbox.

This translation work is cognitive overhead. It’s invisible, unmeasured, and everywhere. We’ve accepted it as the cost of doing business with technology. But here’s the thing about accepted costs: they’re ripe for disruption.

Why This Matters More Than The Next Tech Breakthrough

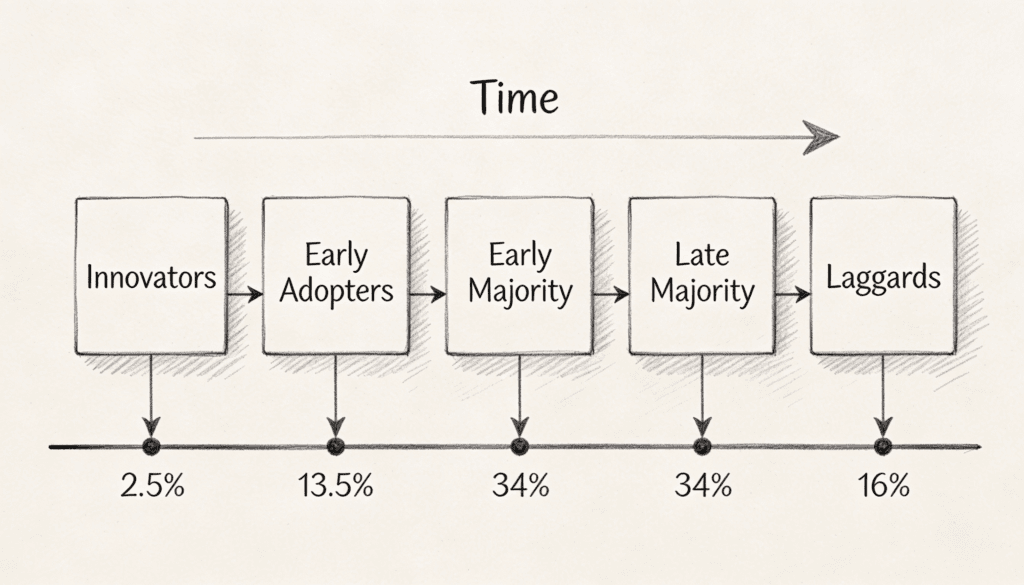

Every major technology platform race eventually ends the same way. The hardware becomes good enough. The software becomes feature complete. Then everyone starts competing on the same axis, and margins compress. Cloud computing providers all offer similar services at similar prices. Project management tools all have the same features. Video conferencing platforms are functionally identical.

This is where cognitive ergonomics enters. It’s not about adding features. It’s about removing friction from thought itself.

Consider how Stripe won the online payments war. PayPal had more users. Banks had more trust. But Stripe understood something nobody else did. Developers didn’t want a full featured payment platform. They wanted to stop thinking about payments entirely. Seven lines of code versus seven hundred. The innovation wasn’t in payment processing technology. It was in cognitive load reduction.

Or look at why Notion captured a generation of knowledge workers despite dozens of competitors with more features. It wasn’t superior note taking technology. It was that Notion reduced the mental taxation of choosing between a document, a spreadsheet, a database, and a wiki. One tool that molds to your thought process instead of four tools that each demand you think their way.

These companies didn’t win by being smarter about payments or documents. They won by being smarter about how people think about payments and documents. That’s cognitive ergonomics paying dividends in market share.

The Three Layers Where Cognitive Friction Hides

Most cognitive overhead lives in three distinct layers. Understanding them is like getting X-ray vision for spotting innovation opportunities.

The first layer is memory taxation. Every tool that requires you to remember where you put something, what you called it, or how you organized it is taxing your memory. Your brain is optimized for pattern recognition and creative synthesis, not for remembering if you saved that file as “Final Draft v3” or “Final Final” or “Use This One.” Yet we’ve built entire systems around the assumption that humans are good at filing and retrieval. We’re not. We’re terrible at it. We only do it because computers demanded it.

The second layer is context switching cost. Your brain needs about 23 minutes to fully settle into deep work after an interruption. Most knowledge workers get interrupted or switch contexts every 11 minutes. We’re living in a permanent state of partial attention, and we wonder why everything feels harder than it should. The tools don’t cause all of this, but they don’t help either. Slack doesn’t know if you’re in deep work. Your calendar doesn’t protect your cognitive state. Your browser doesn’t care that you’re trying to focus.

The third layer is decision fatigue overhead. Every choice a tool forces you to make depletes your decision making capacity. Choosing between three email templates shouldn’t require the same mental energy as choosing a strategic direction. But your brain doesn’t distinguish much between big and small decisions. It just spends energy on all of them. Death by a thousand micro decisions.

The Adjacent Innovation Opportunity

Here’s where it gets interesting for anyone building products. Cognitive ergonomics is the ultimate adjacent innovation because it doesn’t require inventing new technology. It requires rethinking existing technology through the lens of how humans actually think.

You don’t need machine learning to reduce memory taxation. You need better defaults and smarter assumptions. When you create a new document, should the tool really ask you what to name it, where to save it, what template to use, and who has access? Or could it make intelligent guesses based on what you’re working on, who you work with, and what you’ve done before?

You don’t need breakthrough algorithms to reduce context switching. You need systems that understand the difference between urgent and important, between a notification that can wait and one that can’t. Most tools treat every ping as equally worthy of your attention. A cognitively ergonomic tool would understand that some things deserve to interrupt your train of thought and most things don’t.

You don’t need artificial general intelligence to reduce decision fatigue. You need fewer choices presented better. The paradox of choice isn’t new, but we keep building tools that maximize options rather than optimize for outcomes. A cognitively ergonomic approach would hide complexity by default and reveal it only when needed.

What This Looks Like In Practice

The most successful products of 2026 aren’t necessarily doing anything technically impressive. They’re just respecting how human cognition works.

Take the explosion of “ambient” productivity tools. These apps don’t ask you to track your time, categorize your tasks, or estimate your effort. They just watch what you do and learn your patterns. When you open your code editor on Friday afternoons, the tool knows you’re probably doing experimental work, not production deployments. When you have four browser tabs open to the same topic, it knows you’re researching and offers to compile the information. No logging required. No categorization needed.

Or consider the new generation of communication tools that separate time sensitive messages from everything else. Not through manual labeling or complex rules. Just by understanding that “can you review this before the 3pm meeting” is fundamentally different from “here’s an interesting article.” One needs immediate attention. The other can wait. Your brain knows this instantly. Your inbox doesn’t.

Even in hardware, we’re seeing this shift. The latest generation of displays doesn’t just refresh faster or show more colors. They adjust their behavior based on what you’re doing. Reading text? The screen subtly shifts to reduce eye strain. Watching video? Different optimization. Your eyes don’t notice the changes, but your brain does. At the end of the day, you’re less tired. That’s cognitive ergonomics in silicon.

The Counterintuitive Part

Here’s what makes cognitive ergonomics particularly interesting as an innovation strategy. The best improvements often make technology seem dumber, not smarter.

A truly cognitively ergonomic search function might return three results instead of three thousand. That seems worse by traditional metrics. More results equals better search, right? But three carefully chosen results that directly answer your question require less mental processing than scanning through pages of possibilities. Less is more when it comes to cognitive load.

The same principle applies to customization. We’ve spent decades adding settings and preferences to software, operating under the assumption that more control equals better user experience. But every setting is a decision. Every preference is something to think about. A cognitively ergonomic tool might have fewer options, not more. It might just work the right way without asking.

This creates a design challenge that goes against every instinct of the engineering mindset. Engineers solve problems by adding capability. Cognitive ergonomics solves problems by removing choices. It’s subtraction as innovation, which feels wrong until you use the result.

Why The Timing Is Right

Three converging trends make 2026 the inflection point for cognitive ergonomics as a competitive advantage.

First, we’ve hit peak feature bloat. Every category of software has more features than anyone uses. Microsoft Word has thousands of functions. Most people use about twenty. The marginal value of the next feature is approaching zero. But the marginal value of making existing features easier to use? Still enormous.

Second, the AI tooling layer is finally mature enough to enable cognitive ergonomics at scale. You can now build systems that learn individual work patterns without requiring explicit configuration. The technology to watch what users do and adapt to their thinking style exists and is affordable. Five years ago, this required a research team and millions in compute. Today, it’s an API call.

Third, there’s a growing recognition that attention and cognitive capacity are limited resources. The “always on” culture is producing burnout at unprecedented rates. Tools that promise to reduce mental overhead aren’t just nice to have. They’re becoming essential for companies that want to keep their people functional. Cognitive ergonomics is shifting from luxury to necessity.

The Business Model Implications

If cognitive ergonomics is the new frontier, what does that mean for how companies should think about building and selling products?

The traditional software business model is feature velocity. Ship more features, charge more money. But cognitively ergonomic products might have fewer features than competitors. So how do you justify premium pricing?

The answer is outcomes over outputs. A cognitively ergonomic tool might do less, but it helps users accomplish more. Stripe doesn’t have as many payment features as traditional payment processors. But developers using Stripe ship payment integration in hours instead of weeks. That time savings is worth far more than a longer feature list.

This shifts the entire value proposition. Instead of selling capabilities, you’re selling cognitive surplus. Instead of marketing what your product can do, you market what your product lets users stop thinking about. It’s a fundamentally different conversation.

It also changes how you measure success. Traditional software metrics are about adoption and engagement. How many users? How many sessions? How much time in the app? But for cognitively ergonomic products, success might mean less time in the app, not more. If your tool helps someone accomplish their goal in five minutes instead of fifty, that’s a win even though engagement metrics look worse.

The Challenge For Incumbents

Large technology companies face a particular challenge with cognitive ergonomics. Their entire product development culture is built around adding value through features. Revenue projections are based on feature roadmaps. Teams are measured on what they ship. The whole system is optimized for more.

Cognitive ergonomics requires optimizing for less. It requires saying no to features that customers request. It requires removing things that technically work. It means disappointing power users who want every option exposed. This is culturally very difficult for companies built on feature accumulation.

This creates the classic innovator’s dilemma opening. Startups with nothing to lose can build from the ground up around cognitive ergonomics. They can make the hard choices about what to leave out. They can design for the way people think rather than retrofitting thought patterns onto existing architecture. Meanwhile, incumbents are stuck adding “simplicity” as a feature on top of their existing complexity.

Where This Goes Next

The next wave of cognitive ergonomics innovation won’t be in standalone tools. It’ll be in the connective tissue between tools. The average knowledge worker uses something like eleven different applications every day. Each context switch between tools carries cognitive overhead. Each different interface pattern requires mental adjustment. Each separate login, each distinct notification system, each unique keyboard shortcut adds friction.

The companies that figure out how to make multiple tools feel like one continuous cognitive environment will capture enormous value. Not through acquisition and forced integration. Through genuine understanding of how people move between tasks and contexts throughout their day.

We’ll also see cognitive ergonomics applied to AI interfaces. Right now, working with AI tools requires learning prompt engineering, understanding token limits, managing conversation context. These are all forms of cognitive overhead. The next generation of AI products will hide this complexity entirely. You won’t prompt an AI. You’ll just think out loud, and the system will understand what you need.

The Bottom Line

Cognitive ergonomics isn’t a feature category. It’s a design philosophy that recognizes a simple truth: the limiting factor in technology’s value is no longer what computers can do. It’s what humans can think about.

The adjacent innovation opportunity is enormous precisely because it’s adjacent. You don’t need to invent new technology. You need to reinvent how existing technology respects human cognition. That’s a lower technical bar but a higher design bar. It’s not about building better tools. It’s about building tools that let humans be better.

The companies that win the next decade won’t be the ones with the most advanced technology. They’ll be the ones that make advanced technology feel simple. They’ll be the ones that give us back the cognitive capacity we’ve been spending on interface negotiation and let us spend it on actual thinking instead.

That’s the real innovation frontier. Not artificial intelligence. Human intelligence, finally given room to work the way it was meant to.