Table of Contents

Every business tells itself a story about how it makes money. Most of these stories are variations on themes we’ve seen before, dressed up in new clothes. Understanding these patterns matters because the difference between disruption and distraction often comes down to recognizing which archetype you’re actually building, not which one you claim to be.

The word “disruption” gets thrown around so much that it has lost its bite. Every startup founder swears they’re disrupting something. But disruption isn’t about being different. It’s about rendering the old way of doing things obsolete by changing the fundamental rules of value creation and capture. The business model is where this happens, not in the product itself.

The Unbundler

Some companies win by taking apart what others have glued together. Craigslist unbundled newspapers. Spotify unbundled albums. The pattern repeats because bundling creates inefficiency for customers who only want one piece of the package.

The unbundler identifies situations where people pay for things they don’t want to get the things they do want. Cable television forced you to buy 200 channels to watch five. Music labels made you buy twelve songs to get the two you liked. These inefficiencies represent trapped value waiting for someone to set it free.

What makes unbundling powerful is that it attacks the core economic logic of the incumbent. The bundle exists because it subsidizes unprofitable parts of the business with profitable ones. When someone comes along and cherry picks just the profitable parts, the entire structure collapses. The newspaper couldn’t survive losing classified ads because those ads funded the journalism.

But here’s the twist. Unbundlers almost always become bundlers eventually. Netflix started by unbundling Blockbuster’s physical rental model, then unbundled cable. Now it’s bundling its own content into tiers and adding ads. Amazon unbundled retail, then bundled it back together with Prime. The cycle continues because bundling and unbundling respond to different market conditions. Mature markets accumulate bundles. New technology enables unbundling. Then competition drives rebundling.

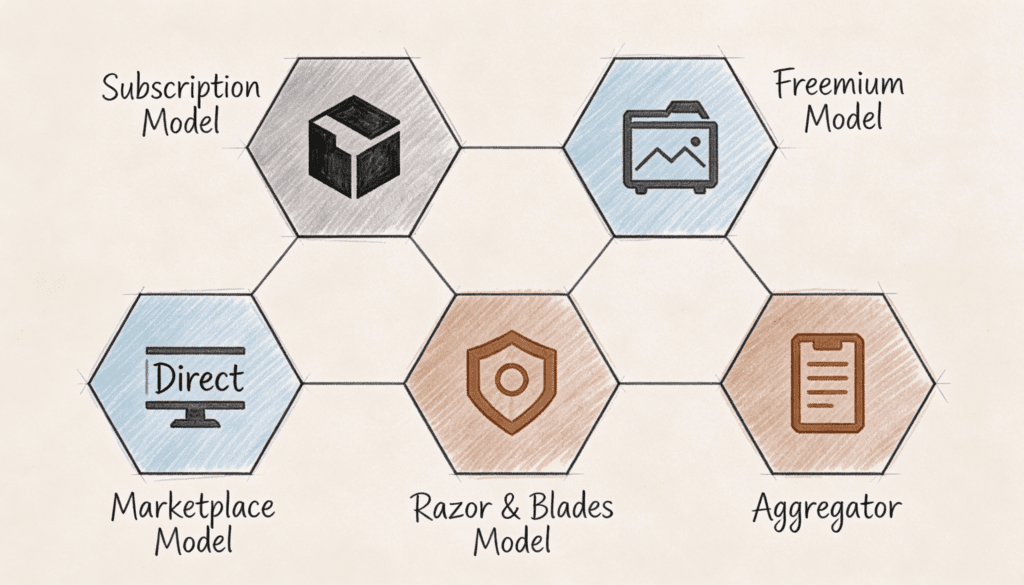

The Aggregator

While unbundlers take things apart, aggregators pull scattered pieces together under one roof. Google aggregates information. Uber aggregates drivers. Airbnb aggregates spare rooms. The pattern works when supply is fragmented and discovery is hard.

Aggregators don’t own the supply. They own the demand. This is crucial. A hotel chain owns its rooms and must manage physical assets. Airbnb owns the platform where people search for rooms, which means it captures value without carrying inventory risk. The leverage is extraordinary.

The aggregator model flips traditional business economics. Normally, controlling supply gives you power. But in networked markets, controlling demand means suppliers have to come to you. Every driver on Uber makes the platform more valuable to riders, which attracts more drivers. The flywheel spins faster as it grows.

This creates winner take most dynamics. The best aggregator in a category tends to dominate because users want to search where the most options exist and suppliers want to list where the most customers are. It’s hard to be the second best aggregator of anything.

The dark side emerges when aggregators become gatekeepers. They started by giving suppliers access to customers they couldn’t reach otherwise. But as the aggregator’s power grows, suppliers become dependent. The platform can then extract more value, change the rules, or insert itself between the supplier and customer. This is why merchants both love and fear Amazon.

The Marketplace

Marketplaces connect buyers and sellers but remain neutral about the transaction. eBay is a marketplace. Etsy is a marketplace. The distinction from aggregators is subtle but important. Aggregators homogenize and control the experience. Marketplaces facilitate diversity and step back.

The marketplace model bets that variety matters more than consistency. If you want something unusual, you’re willing to navigate a messier experience to access a wider range of options. Etsy succeeds because its handmade goods can’t be standardized. eBay works because people want to find specific used items, not generic ones.

Marketplaces face a chicken and egg problem. Buyers won’t come without sellers. Sellers won’t come without buyers. Breaking this deadlock requires creativity. Many successful marketplaces started by serving one side for free or even paying them to participate. OpenTable gave restaurants reservation management software for free to get them on the platform, then charged diners for premium reservations.

The economic challenge for marketplaces is taking a cut small enough that both sides still find the transaction worthwhile, but large enough to build a sustainable business. This is harder than it looks. The marketplace must prove it adds enough value to justify its fee. Otherwise, buyers and sellers will meet on the platform then transact directly to avoid the toll.

The Freemium Model

Freemium gives away the basic product and charges for premium features. Dropbox, Slack, and Spotify all use this approach. The genius is that free users become marketing. Every person using the free version creates exposure and potential conversion.

The model works when the marginal cost of serving another free user approaches zero. Software fits this perfectly. Slack costs almost nothing to let another user send messages. The investment is in building the product once, not in serving each additional user. This means you can be generous with the free tier.

But freemium is a tightrope walk. Make the free version too good and nobody upgrades. Make it too limited and nobody adopts. The conversion rate from free to paid is typically low, often around 2 to 5 percent. This means you need massive scale in free users to generate meaningful revenue.

The best freemium products create natural upgrade triggers. Dropbox gives you limited storage. When your files don’t fit, you pay. Slack limits message history. When you need to search old conversations, you upgrade. The free version becomes genuinely useful, but its limitations emerge through real use, not artificial restrictions.

Here’s what most people miss about freemium. It’s not just about converting free users to paid. Free users provide value even if they never pay. They create network effects. They generate data. They fill out the community. A paid-only product would be lonelier and less useful, which would make it harder to attract even the people willing to pay.

The Subscription Model

Subscriptions trade one time purchases for recurring revenue. Adobe moved from selling Creative Suite to renting it monthly. Microsoft went from boxed Office to Office 365. The financial impact is profound.

Recurring revenue smooths out the feast and famine cycle that project based businesses face. It makes growth predictable. It increases company valuation because investors value predictable cash flows more highly than lumpy ones. A subscription business with the same annual revenue as a traditional business will typically command a much higher multiple.

But subscriptions change the relationship with customers. When someone bought software for $500, the vendor got paid upfront and the relationship effectively ended. With a $20 monthly subscription, the vendor must continuously prove value or the customer churns. The business becomes about retention, not just acquisition.

This shifts where companies invest. Traditional software companies poured resources into sales because that’s where revenue came from. Subscription companies must balance acquisition and retention. Letting customers slip away after you’ve spent money acquiring them is fatal. The unit economics only work if customers stick around long enough to pay back their acquisition cost and then some.

The subscription model also democratizes access. Adobe’s Creative Cloud costs less per month than buying the suite outright cost upfront. This lets people who couldn’t afford the big purchase start using professional tools. The market expands. But it also means professional users who kept software for years now pay continuously. Adobe captured more lifetime value from its best customers by switching models.

The Platform Model

Platforms create value by enabling interactions they don’t directly participate in. Apple’s App Store, AWS, and Shopify are platforms. They provide infrastructure that others build on top of.

The leverage is remarkable. Apple doesn’t make apps, but it captures 30 percent of app revenue. AWS doesn’t build most of the internet, but it hosts much of it. Shopify doesn’t sell products, but it powers millions of online stores. The platform owner takes a slice of activity it enabled but didn’t create.

Platforms benefit from increasing returns to scale. The more developers build apps for iOS, the more valuable iPhones become, which sells more iPhones, which attracts more developers. The same dynamic plays out across platforms. Getting this flywheel spinning early matters enormously.

The risk is disintermediation. If your platform’s main value is connecting parties, those parties might eventually connect directly and cut you out. This is why successful platforms make themselves increasingly difficult to remove. They add features, tools, and services that embed themselves in how participants operate. AWS started by renting computing power. Now it offers hundreds of services that businesses build critical operations around. Switching would be painful enough that most don’t.

Platform businesses also face a governance challenge. They must balance the interests of multiple constituencies. App developers, phone buyers, and Apple itself don’t always want the same things. Too much control and the platform alienates participants. Too little and quality suffers or bad actors exploit the system. Finding this balance determines whether a platform thrives or fragments.

The Razor and Blades Model

This archetype sells something cheap or even at a loss, then makes money on the refills. Printers and ink cartridges. Gaming consoles and games. The initial purchase hooks customers into an ecosystem where the vendor controls the ongoing purchases.

The model creates switching costs. Once you own a Gillette razor, buying Gillette blades is convenient. Switching to a different system means replacing your initial investment. This lock-in lets the company charge higher margins on the blades than competitive markets would normally allow.

But the internet has attacked razor and blade models relentlessly. Subscription services for generic razor blades emerged and undercut Gillette. Third party ink cartridges became easy to find online. The lock-in weakens when customers can easily price compare and access alternatives. The model still works, but requires stronger defenses than it once did.

Some modern companies invert the model. Tesla sells expensive cars but offers free software updates that add features. Apple sells premium iPhones but makes iCloud storage and services cheap. The inversion signals confidence. We make great hardware, so we’ll profit there and be generous with the rest. This builds loyalty differently than the traditional approach, which can feel exploitative.

The Licensing Model

Licensing lets you make money from intellectual property without manufacturing or distribution. Qualcomm licenses chip designs. ARM licenses processor architecture. Disney licenses characters. The model scales beautifully because you create once and sell many times.

The challenge is enforcement. If people can copy your intellectual property without paying, your business collapses. This is why licensing works best with strong legal protection or technical barriers. You need patents, trademarks, or code that others can’t easily replicate.

Licensing also requires restraint. The licensor must resist the temptation to compete with its licensees. ARM succeeded partly because it stayed neutral. It designed processors but didn’t manufacture them, so chip makers trusted partnering with ARM wouldn’t make them a competitor. Compare this to Microsoft’s attempt to make its own Surface tablets while licensing Windows to PC makers. The conflict created tension.

Combining Archetypes

Real companies rarely use just one archetype. Amazon is an aggregator for third party sellers, a subscription business with Prime, a platform with AWS, and increasingly a manufacturer with private label products. Understanding the taxonomy helps identify which archetype drives the core business and which play supporting roles.

Mismatching archetypes can destroy value. A company structured as a subscription business that tries to act like a marketplace will struggle. The incentives don’t align. Subscriptions need retention and consistent value delivery. Marketplaces need liquidity and variety. Trying to optimize for both pulls in different directions.

The most interesting strategic decisions happen at the intersections. Should a marketplace become a subscription business by offering premium memberships? Should an aggregator start manufacturing to control supply? These moves change what game you’re playing and who you’re competing against.

The Lifecycle of Archetypes

Business model archetypes aren’t static. What works in growth phase differs from maturity. Aggregators often start by subsidizing one side of the market to solve the chicken and egg problem. Once they dominate, they shift to extracting value. The archetype hasn’t changed, but the tactics and positioning have.

Some archetypes naturally evolve into others. Many subscription businesses started as platforms. Platforms need users before subscriptions make sense. Build the community first, monetize it second. Other evolutions are forced by competition. When everyone in your category adopts freemium, you might need to as well just to get trials.

Understanding where an archetype typically leads helps with long term planning. If you’re building an unbundler, prepare for the bundling phase. If you’re launching a marketplace, anticipate the pressure to become an aggregator by homogenizing supply. These evolutions aren’t inevitable, but they’re common enough to plan for.

The taxonomy of disruption isn’t about fitting every company into a neat box. It’s about recognizing patterns that have worked before and understanding why they worked. The mechanics of value creation and capture repeat across industries and eras because human behavior and economic incentives remain relatively stable.

New technology enables new variations on these archetypes, but truly novel business models are rare. Most “disruption” is actually the application of a proven archetype to a new domain where it hasn’t been tried yet. The innovation is in the execution and adaptation, not the fundamental pattern.

This is actually liberating. You don’t need to invent a completely new way of making money. You need to identify which proven archetype fits your opportunity and execute it better than anyone else has in your space. Understanding the taxonomy gives you a vocabulary for that conversation and a framework for making strategic choices.

The companies that matter most tend to master one archetype so thoroughly that they redefine how value works in their category. Then they carefully add others without diluting what made them successful in the first place. That’s the real art of business model design.