Table of Contents

Many business conferences has similar origin story. Someone in a black turtleneck walks onto stage and tells us to think different. To disrupt. To be visionary. To channel our inner Steve Jobs and revolutionize industries through sheer force of genius.

Then we all go back to our offices and realize we’re not Steve Jobs. We don’t have his taste, his timing, or his reality distortion field. Worse, we’re trying to innovate in industries where being a lone genius is actually counterproductive.

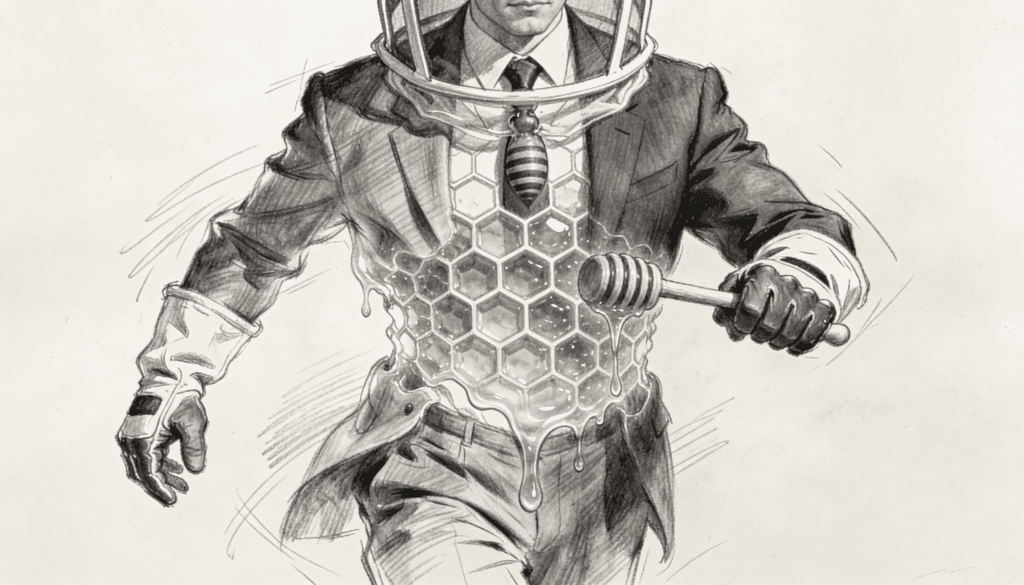

Here’s what nobody tells you: the most powerful innovations don’t come from isolated visionaries. They come from promiscuous idea sharing across unrelated domains. They come from accidental collisions between fields that have no business talking to each other. They come, in other words, from acting less like a tech CEO and more like a beekeeper.

Beekeepers don’t create honey. They create conditions for cross pollination. They understand that their job isn’t to be brilliant but to facilitate the movement of genetic material between flowers that would never naturally meet. The magic happens in the transfer, not in the master plan.

This is cross pollination innovation, and it’s responsible for more breakthroughs than genius ever was.

The Biology Lesson That Explains Everything

When a bee visits a flower, it’s not trying to innovate. It’s looking for nectar. The pollen that sticks to its legs is accidental cargo. When that bee visits another flower across the garden, it transfers genetic material between two plants that might be separated by distance, timing, or pure circumstance. The result is hybrid vigor, genetic diversity, and fruits that wouldn’t exist otherwise.

The innovation happens in the gap between visits. It happens because the bee doesn’t discriminate. It visits the rose and then the tomato plant. It moves between the exotic orchid and the common dandelion. It doesn’t have a strategy. It just moves.

Now look at how most organizations try to innovate. They put smart people in a room with other smart people from the same field. Engineers talk to engineers. Marketers talk to marketers. The finance team stays in their lane. Everyone reads the same industry publications, attends the same conferences, and benchmarks against the same competitors.

This is the equivalent of keeping bees in a garden with only one type of flower. You might get efficient pollination within that species, but you’ll never get anything genuinely new.

When a Musician Redesigned the Hospital

Martin Bromiley was an airline pilot, not a doctor. His wife Elaine died during a routine medical procedure in 2005 because of failures in communication and decision making during an anesthesia crisis. The medical team had the skills to save her. They had the equipment. What they didn’t have were the teamwork protocols that aviation had developed over decades.

Bromiley could have been angry and helpless. Instead, he became a bee. He took concepts from aviation safety, cockpit resource management, and checklist protocols, and he carried them into operating rooms. The Clinical Human Factors Group he founded has since transformed how medical teams communicate during crises.

The innovation wasn’t medical. It was translational. Nobody in healthcare was going to invent cockpit resource management because they were too busy trying to solve medical problems with medical thinking. It took someone carrying pollen from a completely different garden.

This happens more than we admit. The assembly line came from meatpacking, not automotive manufacturing. The Fosbury Flop high jump technique came from a kid who wasn’t coached in traditional methods.

The pattern is obvious once you see it. Innovation accelerates at the borders between disciplines, not at their centers.

Why Experts Are Terrible Pollinators

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: expertise makes you worse at cross pollination innovation, not better.

When you spend years mastering a domain, you develop mental models that are incredibly useful for solving problems within that domain. You learn what works. You learn what doesn’t work. You learn what questions are worth asking and which are wastes of time.

But you also learn what’s “obviously” impossible. You learn what “everyone knows” doesn’t work. You learn to see problems through a very specific lens, and that lens filters out solutions from other fields as irrelevant or naive.

Psychologists call this functional fixedness. You become so good at using a hammer that everything starts looking like a nail, and you stop noticing that sometimes you need a screwdriver.

The expert sees a medical problem and thinks about medical solutions. The outsider sees a medical problem and thinks, “This looks like the communication breakdown I saw in airline cockpits.” The expert has depth. The outsider has range. And for cross pollination, range matters more.

This doesn’t mean expertise is worthless. It means expertise needs to be in conversation with non expertise. The best innovations come from teams where someone knows the problem deeply and someone else knows nothing about it at all but knows something completely different very well.

The Architecture of Accidental Collision

If cross pollination innovation happens at the borders between fields, the question becomes: how do you increase the amount of border territory in your organization?

Most companies are organized for efficiency, not for collision. Departments are siloed. Meetings are focused. Everyone has clear responsibilities. This is great for execution. It’s terrible for innovation.

The alternative is to design for productive randomness. This sounds chaotic, but it’s actually quite structured.

At Bell Labs in its golden age, researchers from wildly different fields shared the same long corridors and the same cafeterias. A physicist would walk past a mathematician’s office on the way to lunch. A conversation about noise in telephone lines would spark an insight about quantum mechanics. The building itself was a pollination mechanism.

Pixar’s Steve Jobs (yes, that one) designed their headquarters with a similar principle. He put the bathrooms, mailboxes, and cafeteria in the center of the building so that people from different departments would be forced to cross paths. Animators would bump into engineers. Writers would chat with rendering specialists.

This isn’t about forced fun or mandatory brainstorming. It’s about increasing the likelihood that people with different mental models end up in the same room talking about the same problem.

Some companies do this through rotation programs where employees spend time in different departments. Others create project teams that deliberately mix disciplines. Still others host internal conferences where anyone can present ideas from their field to non specialists.

The method matters less than the principle: you want to maximize the surface area between different knowledge domains.

The Reading List Method

You don’t need to restructure your entire office to practice cross pollination thinking. You can start with what you read.

Most professionals consume information from within their industry. Marketers read marketing blogs. Engineers read engineering journals. This makes sense for staying current, but it’s pollination within the same flower.

Try this instead: for every book or article you read about your field, read one from a completely unrelated domain. If you’re in finance, read about evolutionary biology. If you’re in software development, read about urban planning. If you’re in healthcare, read about game design.

The goal isn’t to become an expert in everything. The goal is to fill your mind with patterns and mental models from other domains that you can remix when you encounter problems in your own.

Frans Johansson calls this the Medici Effect, after the family that sparked the Renaissance by bringing together creators from different disciplines in Florence. The innovations didn’t come from any single field. They came from the intersections.

You’re looking for structural similarities between unrelated problems. How is managing a supply chain like managing an ecosystem? How is designing a user interface like choreographing a dance? How is financial risk management like epidemiology?

These analogies sound silly until one of them unlocks a solution that nobody in your field would have thought of.

When Constraints Force Cross Pollination

Sometimes the best innovations come from necessity, not from deliberate pollination strategies.

During World War II, the British government needed to get more nutrition into a population facing rationing. The Ministry of Food couldn’t solve this with traditional nutrition science alone. So they borrowed from advertising and propaganda. They created campaigns that made vegetables patriotic. They turned scarcity into a creative constraint that led to recipes and growing techniques that persisted long after the war ended.

Constraints force you to look outside your domain because the tools inside your domain aren’t sufficient. This is why startups often out innovate established companies. They don’t have the resources to solve problems the traditional way, so they have to pollinate.

The lesson here is that you can create productive constraints deliberately. What if you couldn’t use the obvious solution? What if you had half the budget? What if you had to solve this problem using only tools from a completely different industry?

These aren’t real constraints, but they force the same kind of cross pollination thinking that real constraints do.

The Danger of Pollination Theater

Not all cross pollination actually works. In fact, most of it doesn’t.

There’s a growing industry of innovation consultants who will come to your company, put sticky notes on walls, and ask your team to “think like a designer” or “approach this like an entrepreneur.” This is pollination theater. It’s the appearance of cross disciplinary thinking without the substance.

Real cross pollination requires deep enough understanding of another field to recognize transferable patterns. You can’t just sprinkle design thinking fairy dust on a logistics problem and expect magic.

The other risk is what happens when you bring in an outsider who doesn’t respect the domain knowledge of the insiders. The outsider sees the healthcare system and says, “Why don’t you just do it like we do in tech?” without understanding the regulatory complexity, the life and death stakes, or the decades of hard won knowledge about what actually works with patients.

Effective cross pollination isn’t about replacing domain expertise with outside thinking. It’s about creating dialogue between them. The bee doesn’t destroy the flower. It works with the flower’s existing structure to create something new.

Building Your Pollination Network

If you’re serious about this approach, you need to deliberately build a network that spans different domains.

This doesn’t mean collecting business cards at conferences. It means developing genuine relationships with people who think differently than you do. People in different industries. People with different educational backgrounds. People who read different books and solve different problems.

The value of these relationships isn’t that you can “pick their brain” when you need a favor. The value is that regular exposure to how they think changes how you think.

Your network is your garden. The more diverse your garden, the more interesting the pollination.

The Uncomfortable Truth About Original Ideas

Here’s something that will either liberate you or depress you: there are no truly original ideas.

Every innovation is a recombination of existing elements. Steve Jobs didn’t invent the graphical user interface or the mouse. He saw them at Xerox PARC and combined them with his ideas about consumer electronics and design simplicity. The iPhone combined existing technologies (touchscreens, mobile phones, internet connectivity, music players) in a new configuration.

This isn’t criticism. This is how innovation actually works. It’s not divine inspiration. It’s promiscuous borrowing and creative recombination.

Once you accept this, the pressure to be a lone genius disappears. You’re not trying to conjure something from nothing. You’re trying to be in the right place at the right time with the right combination of influences.

You’re trying to be a bee.

What This Means for You Tomorrow

Stop trying to be the smartest person in the room. Start trying to be in rooms with people who know things you don’t.

Stop reading only industry publications. Start reading things that seem irrelevant to your work.

Stop organizing teams by functional expertise. Start creating projects that force different disciplines to collaborate on the same problem.

Stop benchmarking only against competitors. Start studying how completely different industries solve analogous problems.

Stop protecting your idea from outside input. Start exposing it to people who will see it differently than you do.

The beekeeper doesn’t tell the bee where to go. The beekeeper creates an environment where productive pollination becomes inevitable. You’re not trying to control the innovation process. You’re trying to increase the odds that useful collisions happen.

This is humbler than the genius narrative we’re sold. It’s also more honest about how breakthrough innovation actually occurs.

The next time someone tells you to think different, ask them which gardens they’re visiting. Ask them who they’re learning from outside their field. Ask them what their last good idea borrowed from.

If they can’t answer those questions, they’re not actually innovating. They’re just repeating the same ideas in a louder voice.

Be the bee instead. Visit strange gardens. Carry pollen between worlds that don’t usually talk to each other. Create the conditions for accidental brilliance.

The honey will take care of itself.

Pingback: 7 Habits of Highly Innovative Departments