Table of Contents

Every year, someone declares that a new technology will change everything. Virtual reality was supposed to transform how we socialize. Blockchain would eliminate middlemen. AI would take all our jobs. Yet here we are, still commuting to offices, using centralized platforms, and very much employed.

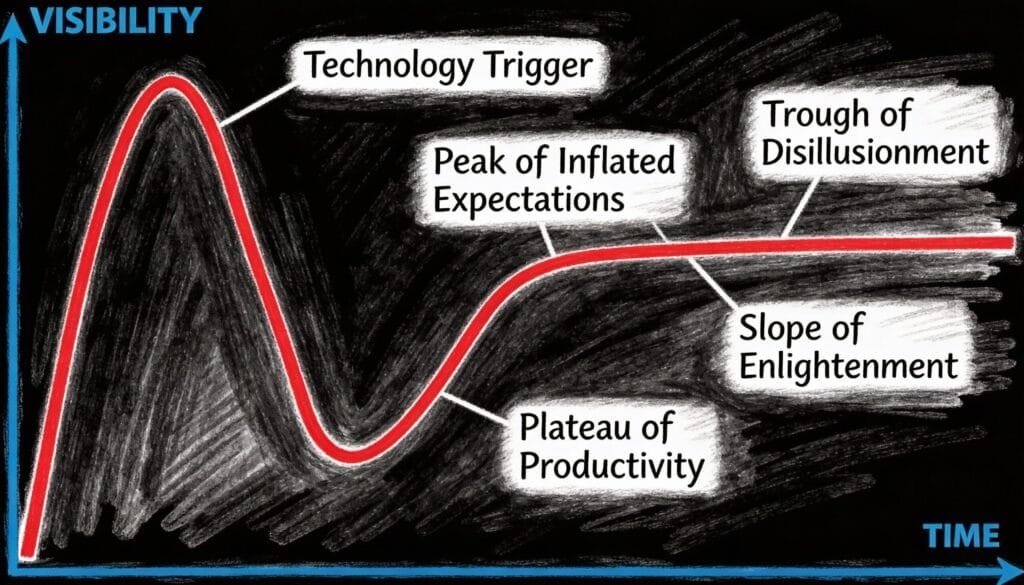

This pattern of wild optimism followed by crushing disappointment followed by quiet usefulness isn’t random. It’s so predictable that Gartner, the research firm, mapped it into five distinct stages. They call it the Hype Cycle, and understanding it might be the most valuable framework for anyone trying to make sense of technological change.

The cycle reveals something profound about human nature. We’re terrible at predicting the future, not because we lack information, but because we swing between irrational exuberance and unwarranted despair. The technology itself often remains fairly constant. What changes is our emotional relationship to it.

The Innovation Trigger: When Lightning Strikes

The first stage begins with a breakthrough. A lab publishes a paper. A startup demos something impossible. A researcher makes neurons fire in a petri dish. This is the Innovation Trigger, the moment when something genuinely new enters the world.

What makes this stage fascinating is how small it actually is. The transistor, which enabled every digital device you own, was demonstrated to a handful of people in a small room. CRISPR gene editing emerged from studying how bacteria fight off viruses.

The innovation itself is usually crude. Early airplanes barely flew. The first computer mouse was a wooden box. The initial iPhone didn’t have an app store. But buried in these humble beginnings is genuine novelty. Something previously impossible is now merely difficult.

Here’s the counterintuitive part. The Innovation Trigger stage generates almost no hype. Real breakthroughs happen in obscure journals and university labs. The people who understand the innovation best are often the most cautious about predicting its impact. They know how much work remains.

The technology at this stage is like a newborn. Full of potential, certainly, but also helpless and requiring enormous resources just to survive. Most innovations die here, unknown and unmourned. Only a tiny fraction make it to the next stage.

The Peak of Inflated Expectations: When Everyone Loses Their Mind

If the Innovation Trigger survives, it enters the most dangerous and exciting stage. The media discovers it. Venture capitalists start writing checks. Conference keynotes multiply. Everyone suddenly becomes an expert on something that barely exists.

The Peak of Inflated Expectations is where rationality goes to die. Projections become untethered from reality. A technology that works in a lab under perfect conditions becomes, in the public imagination, ready for mass deployment. A prototype becomes a product. A possibility becomes a certainty.

Consider autonomous vehicles. Around 2015, experts confidently predicted that fully self-driving cars would be common by 2020. Billions of dollars flowed into the sector. Cities began planning for a world without parking lots. The technology was real. The breakthrough had happened. But the gap between “this works on a closed track in Arizona” and “this works everywhere in all weather conditions” turned out to be vast.

This stage reveals something about how information spreads in modern society. Good news travels faster than nuanced news. “Revolutionary new technology will change everything” gets more clicks than “promising development faces significant engineering challenges.” The economic incentives favor hype. Startups need funding. Media needs pageviews. Consultants need speaking fees.

The irony is that excessive hype often damages the technology it claims to promote. When expectations inflate beyond what’s achievable, disappointment becomes inevitable. The bigger the bubble, the harder the crash.

Yet hype serves a purpose. It attracts attention, talent, and capital. Technologies need resources to develop. The Peak of Inflated Expectations, for all its absurdity, funds the research that moves innovation forward. It’s wasteful and necessary in equal measure.

The Trough of Disillusionment: Where Dreams Go to Die

What goes up must come down. After the peak comes the valley.

The Trough of Disillusionment is where reality reasserts itself. The prototype doesn’t scale. The business model doesn’t work. The technical challenges prove harder than anticipated. Early adopters discover that the revolution they were promised is actually an expensive beta test.

This is the stage where companies fail, investors lose money, and journalists write “whatever happened to” articles. The technology that was going to change everything becomes a punchline. Remember Google Glass? Segways? They all took their turn in the trough.

What’s remarkable is how thoroughly sentiment shifts. The same people who were breathless with enthusiasm become dismissive. The pendulum swings from irrational exuberance to irrational pessimism. A technology that was overhyped at the peak becomes underhyped in the trough.

The trough serves as a filter. It separates genuine innovations from mirages. Technologies with real utility survive. Those built entirely on hype collapse. It’s brutal but effective.

Here’s what most people miss about the trough. This is often when the most important work happens. With the spotlight gone and the tourists departed, serious people solve serious problems. The engineers who remain actually believe in the technology. They’re not there for the hype or the quick exit. They’re there because they see something worth building.

Electric vehicles spent decades in the trough. The idea worked, but batteries were expensive and charging infrastructure didn’t exist. While the world moved on, engineers kept improving battery chemistry, reducing costs, and solving technical problems. By the time Tesla made electric cars cool, the hard work of making them practical was largely done.

The trough is where innovations either die or grow up. Most die. A few emerge stronger, having shed their illusions and proven their worth.

The Slope of Enlightenment: The Long Boring Middle

After the drama of the peak and the despair of the trough comes something unexpected. Quiet, steady progress.

The Slope of Enlightenment is the least exciting stage to observe but perhaps the most important to understand. This is where the real work of turning an innovation into something useful happens. No headlines. No dramatic pivots. Just iteration, refinement, and gradual improvement.

The technology starts working reliably. Use cases become clear. Best practices emerge. The infrastructure develops. Early adopters figure out what works and share their knowledge. The ecosystem matures.

This stage often takes far longer than anyone expects. The internet was invented in the 1960s. It didn’t become mainstream until the 1990s. That’s thirty years on the Slope of Enlightenment. Machine learning has been around since the 1950s. It only became genuinely useful in the 2010s.

Think of the slope as the technology’s adolescence. The rapid growth of childhood is over. The maturity of adulthood hasn’t arrived. It’s the awkward middle period where capabilities slowly expand and reliability gradually improves.

What makes this stage interesting is how invisible it is to most people. The media has moved on. Investors are chasing the next big thing. But for the people actually using the technology, this is when it becomes genuinely valuable. Not revolutionary, just useful.

Cloud computing spent years on this slope. After the initial hype around “everything as a service” faded, companies quietly figured out what cloud was actually good for. Not everything, it turned out. But enough things to build trillion dollar businesses.

The slope rewards patience and punishes impatience. The people who succeed here are those who can maintain focus while everyone else chases novelty. It’s the least glamorous stage but possibly the most profitable.

The Plateau of Productivity: Boring Is Beautiful

The final stage is where innovations become infrastructure. They work so well that we stop noticing them. They’re no longer the future. They’re just the present.

The Plateau of Productivity represents full maturity. The technology has proven itself. Standards exist. Competition has emerged. Prices have fallen. What was once magical has become mundane.

This is simultaneously the most successful and least interesting stage. Successful because the technology has achieved widespread adoption. Uninteresting because there’s nothing left to say. Refrigerators are on the plateau. So are smartphones, email, and GPS. They work. We use them. We’ve moved on.

The plateau reveals the ultimate irony of technological progress. Every revolutionary technology, if successful, becomes ordinary. The personal computer was going to change everything. It did. Now it’s so common that we complain when our laptop boots slowly.

What’s counterintuitive about the plateau is that this is when the technology often has its biggest impact. Not when it’s new and exciting, but when it’s old and reliable. The internet changed more about society after it became boring infrastructure than when it was the hot new thing.

The plateau is where second order effects emerge. The really interesting changes aren’t the obvious ones that everyone predicted. They’re the subtle shifts that nobody saw coming. Nobody predicted that smartphones would kill point-and-shoot cameras. Nobody foresaw that social media would reshape politics. These weren’t first order effects. They were emergent properties of mature technologies.

This final stage also tends to be long. Very long. Electricity has been on the plateau for over a century. We’re still finding new uses for it. The plateau isn’t stagnation. It’s stable enough for people to build on top of it.

Reading the Gartner Hype Cycle

Understanding the Hype Cycle doesn’t just help predict where technologies are heading. It provides a framework for making better decisions about when to adopt, when to invest, and when to wait.

The mistake most people make is timing. They get excited at the peak, when prices are high and expectations unrealistic. They give up in the trough, right before things get interesting. They ignore technologies on the slope because they’re not exciting enough.

Smart organizations do the opposite. They experiment during the Innovation Trigger. They stay skeptical at the peak. They invest during the trough when everyone else has left. They deploy during the slope when the technology actually works.

The cycle also explains why predictions about technology are usually wrong in the details but right in the big picture. Yes, we have video calls. No, we’re not all living in virtual reality. The technology arrived, just not in the form or timeframe anyone predicted.

Perhaps the most valuable insight from the Hype Cycle is that it’s not really about technology at all. It’s about us. Our tendency to overestimate short term change and underestimate long term change. Our emotional swings between optimism and pessimism. Our difficulty thinking in timescales longer than a few years.

Technologies are fairly predictable. Human reactions to technologies are not. The Hype Cycle maps our psychological journey with innovation as much as the innovation’s technical journey.

Where We Are Now

Look around at current technologies and you can place them on the cycle. Large language models and generative AI are somewhere between the peak and the trough. The hype is enormous. The reality is messier. Quantum computing is earlier, still climbing toward its peak. Virtual reality is on its second or third trip through the cycle, having crashed before and slowly rebuilding.

The cycle repeats because human nature doesn’t change. Each generation encounters new technologies and makes the same mistakes. We hype too early. We despair too quickly. We underestimate how long useful change takes.

But recognizing the pattern gives us power. We can choose to be less swayed by hype at the peak and less despairing in the trough. We can learn to focus on the technologies quietly climbing the slope rather than those dominating headlines.

The Hype Cycle reminds us that innovation is a marathon, not a sprint. The finish line isn’t the demo or the funding announcement or the IPO. It’s the quiet moment, years or decades later, when the technology becomes so integrated into daily life that we forget it was ever new.

That’s when you know something has truly changed the world. Not when everyone’s talking about it, but when nobody needs to talk about it anymore.