Table of Contents

Let’s be honest about corporate innovation: we preach radical thinking but practice incremental adjustments. Our innovation frameworks and ideation sessions mostly generate variations on familiar themes. Meanwhile, biomimicry offers access to 3.8 billion years of nature’s R&D breakthroughs, yet we walk right past this laboratory toward another whiteboard session.

Nature isn’t just a source of inspiration for feel-good metaphors about organizational ecosystems. It’s a catalog of solved engineering problems, tested business models, and strategies that have survived the most brutal market testing imaginable: extinction. When a Chief Innovation Officer learns to read this catalog, something shifts. The questions change from “What can we invent?” to “What has already been solved?”

The Problem with Innovation Theater

Most organizations approach innovation like they’re searching for buried treasure without a map. They know it exists somewhere, they’re willing to dig, but they’re essentially making educated guesses about where to start. This produces what we might call innovation theater: activities that look like innovation, feel like innovation, and consume innovation budgets, but rarely produce breakthrough results.

Consider the typical corporate innovation process. Teams gather in rooms with whiteboards. Someone suggests we need to “think differently.” Ideas emerge that are usually either too safe or too disconnected from actual market needs. The safe ideas get implemented and produce marginal improvements. The wild ideas get shelved for being impractical. The cycle repeats.

Biomimicry offers something different: a systematic method for finding solutions that have already been stress tested. It’s not about copying nature superficially. It’s about understanding the principles behind natural solutions and translating them into human challenges.

Reading Nature’s Patent Portfolio

Evolution is a terrible designer in the moment but an extraordinary optimizer over time. It has no grand vision, no five year plan, no quarterly targets. It simply runs endless experiments, keeps what works, and discards what doesn’t. The result is a vast library of solutions to problems that transcend biology: How do you move efficiently? How do you build strong structures with minimal materials? How do you process information without a central command system? How do you adapt to changing conditions?

Take the example of Shinkansen, Japan’s bullet train. Engineers faced a specific problem: when the train emerged from tunnels at high speed, it created sonic booms that violated noise pollution regulations. Traditional engineering approached this as an aerodynamics problem requiring computer modeling and wind tunnel testing.

Then an engineer who happened to be a birdwatcher noticed something. Kingfishers dive into water to catch fish without creating a splash, despite the dramatic change in medium. The bird’s beak shape allows this seamless transition. The train’s nose was redesigned based on the kingfisher’s beak. The result wasn’t just quieter. The train became faster and used less electricity. One biological principle solved multiple engineering challenges simultaneously.

This isn’t an isolated success story. It’s a pattern. When you understand how nature solves problems, you often find solutions that are more elegant, more efficient, and more sustainable than conventional engineering approaches.

Why CIOs Miss This

Chief Innovation Officers live in a world of quarterly reviews, board presentations, and competitive pressure. This creates a particular kind of blindness. When your job is to produce innovation on a schedule, you naturally gravitate toward approaches that promise predictable results. Biomimicry seems fuzzy by comparison. How do you put “study how beetles collect water in the desert” on a Gantt chart?

This misses the point entirely. Biomimicry isn’t about adding nature studies to your innovation process. It’s about recognizing that many of the problems your organization faces aren’t actually new. They’re variations on challenges that organisms have been solving for eons. Your role as a CIO isn’t to invent solutions from scratch. It’s to be a translator between biological principles and business challenges.

The other barrier is aesthetic. Biomimicry can sound like hippie science, something for companies that want to appear environmentally conscious but not necessarily effective. This is a profound misunderstanding. The US military invests heavily in biomimicry research. So do tech giants, manufacturing companies, and financial firms. They’re not doing this for public relations. They’re doing it because it produces results that traditional R&D misses.

The Namibian Fog Beetle and Material Science

Let’s get specific about how this works in practice. The Namibian fog beetle lives in one of the driest places on Earth. It survives by collecting water from morning fog using its back, which has a specific pattern: hydrophilic bumps surrounded by hydrophobic channels. Water condenses on the bumps and rolls down the channels directly into the beetle’s mouth.

Material scientists studying this beetle developed new surfaces for collecting water, but the applications went further. One organism’s survival strategy became a platform technology with applications across multiple industries.

This reveals something important about how biomimicry works for innovation. You’re not looking for direct analogies. You’re looking for principles. The beetle isn’t teaching us how to collect fog specifically. It’s teaching us about managing surface properties at a micro scale to control liquid behavior. That principle applies anywhere you need to move, collect, or repel liquids.

Networks Without Hierarchy

Corporate innovation often stumbles on organizational structure. Who owns the innovation process? How do you coordinate across departments? How do you make decisions quickly without creating bottlenecks? We treat these as management problems requiring careful organizational design.

Slime molds offer a different perspective. These organisms have no central nervous system, no brain, no hierarchy. Yet they solve complex problems like finding the shortest path between food sources, essentially recreating efficient transportation networks that mirror human-designed subway systems. They do this through simple local rules followed by individual cells, with no top-down coordination.

Japanese researchers used slime mold behavior to optimize railway networks. They placed food sources at locations corresponding to cities around Tokyo and watched how the slime mold created connections. The resulting pattern was remarkably similar to the existing rail network, but with some interesting differences that suggested potential improvements.

For a Chief Innovation Officer, the lesson isn’t about slime molds specifically. It’s about recognizing that effective networks don’t require central control. They require good local rules and feedback mechanisms. This has implications for how you structure innovation teams, how you allocate resources, and how you allow ideas to spread through an organization.

The Termite Mound and Climate Control

Eastgate Centre in Harare, Zimbabwe, maintains comfortable temperatures year round with no conventional air conditioning. The building uses 90% less energy for climate control than comparable structures. The design is based on termite mounds, which maintain constant internal temperatures despite extreme external fluctuations.

Termites achieve this through a complex system of vents and tunnels that create passive airflow. Hot air rises and exits through the top while cool air enters from the bottom and through underground tunnels. The system is entirely passive, requiring no energy input beyond the physics of convection.

The architect who designed Eastgate Centre didn’t copy the mound’s appearance. He understood the principle: using building geometry and material properties to create natural airflow. The building looks nothing like a termite mound but functions on the same thermal regulation principles.

This distinction matters for innovation. Biomimicry isn’t biomimicking. You’re not making buildings that look like termite mounds or trains that look like bird beaks. You’re extracting functional principles and applying them to human contexts. The visual similarity is irrelevant. The functional similarity is everything.

Failure as Information

Nature’s approach to failure is instructive for innovation culture. In biological evolution, most mutations fail. Most new species go extinct. Most experiments don’t work. This isn’t a problem. It’s the process. Failure is information about what doesn’t work in a particular environment under specific conditions.

Corporate innovation, by contrast, often treats failure as something to be minimized or hidden. Projects that don’t succeed become political liabilities. Teams learn to avoid risks that might lead to visible failures. This is precisely backward if you actually want innovation.

Biomimicry suggests a different approach: rapid, cheap experimentation with clear success criteria and quick decisions about what to pursue. Nature doesn’t throw good money after bad. When something doesn’t work, it gets discontinued. When something shows promise, resources flow toward it. There’s no ego involved, no sunk cost fallacy, no political maneuvering to keep failed projects alive.

For CIOs, this means creating space for small experiments that can fail without consequences, while maintaining clear standards for what constitutes success. It means borrowing nature’s bias toward action over analysis. Try things. See what works. Move on quickly from what doesn’t.

Ecosystems and Competition

Business strategy often frames competition in zero sum terms. You win market share by taking it from competitors. Your gain is their loss. This creates a particular approach to innovation: How do we beat our rivals?

Natural ecosystems reveal a more complex picture. Yes, competition exists. But so does cooperation, symbiosis, and niche specialization. Most organisms don’t try to dominate entire ecosystems. They find specific roles where they can thrive while depending on and supporting other species.

Coral reefs demonstrate this vividly. They’re some of the most biodiverse ecosystems on Earth, supporting thousands of species in relatively small areas. This works not through dominance but through specialization and mutualism. Each organism occupies a specific niche, often depending on others for survival while providing benefits in return.

The innovation parallel is about finding your organization’s actual competitive advantage rather than trying to do everything. What specific problem can you solve better than anyone else? What capabilities do you have that create unique value? Instead of competing head to head with larger rivals, what niche can you dominate?

This also suggests looking for partnership opportunities that conventional competitive thinking misses. What other organizations have complementary capabilities? Where can you create value together that neither could create alone?

Materials Science and the Strength of Weakness

Spider silk is stronger than steel by weight yet flexible enough to absorb massive impacts without breaking. This inverts conventional thinking about innovation in materials and product design. We tend to look for better ingredients: stronger metals, more durable plastics, advanced composites. Nature often works with ordinary materials arranged in extraordinary ways.

For innovation leaders, this suggests questions about organizational structure and process design. Are you trying to solve problems by finding better people, or by arranging the people you have in better ways? Are you looking for revolutionary technologies, or for novel combinations of existing capabilities?

The principle extends beyond materials. How do you create organizational resilience? Not by making every component indestructible, but by designing systems that can absorb shocks, distribute stress, and recover from damage. Nature doesn’t build things that never break. It builds things that break gracefully and repair effectively.

The Practice of Seeing Differently

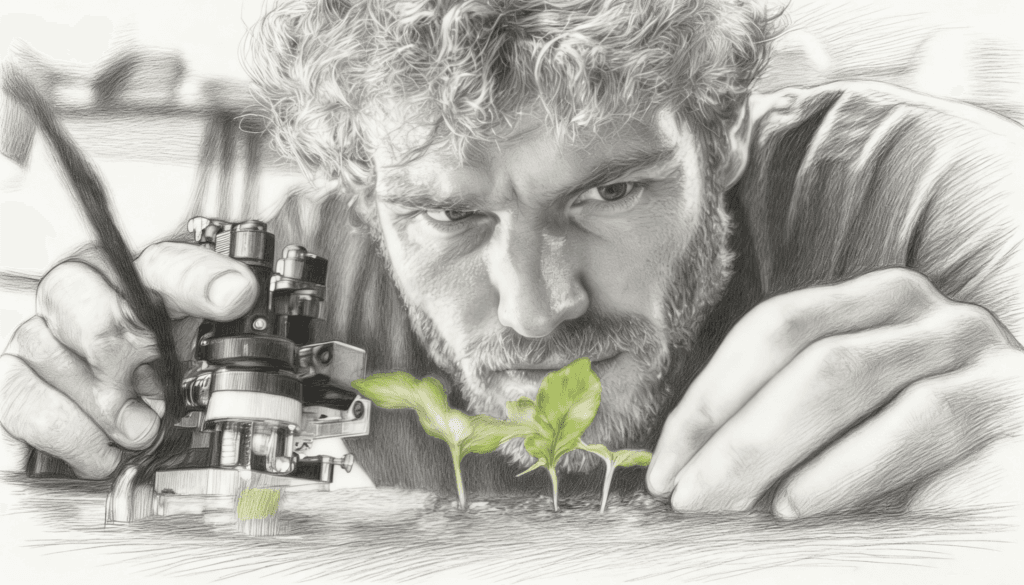

Understanding biomimicry as a Chief Innovation Officer isn’t about taking a biology course or hiring scientists. It’s about developing a different way of seeing problems. When you face an innovation challenge, the first question becomes: Has nature solved anything like this?

This requires building connections between biological knowledge and business challenges. It means creating spaces where people with different expertise can translate between domains. The engineer who solves a fluid dynamics problem might need to talk with someone who studies how fish schools move through water. The team designing an organizational structure might benefit from understanding how ant colonies coordinate without central planning.

The practical implementation involves several steps. First, clearly define the function you’re trying to achieve, stripped of preconceptions about how it should work. Not “we need a faster motor” but “we need to convert energy into rotational motion efficiently.” Second, identify organisms or ecosystems that perform similar functions. Third, understand the biological mechanisms at the principle level, not just the surface appearance. Fourth, abstract those principles into design concepts. Fifth, test and iterate.

This process isn’t mystical or purely creative. It’s systematic. Organizations like the Biomimicry Institute have developed databases and methodologies for this kind of functional mapping between biological solutions and human challenges.

Beyond Sustainability

Biomimicry is often positioned as primarily about environmental sustainability, and it does have significant implications there. Natural systems are inherently circular, waste is food for other processes, and energy comes from renewable sources. These are important considerations.

But limiting biomimicry to sustainability misses its broader value for innovation. Nature is a source of solutions to any problem involving materials, structures, information processing, energy management, network design, adaptation, or resource allocation. Most business challenges fall into these categories.

The environmental benefits often arrive as side effects of better design. When you optimize for efficiency the way nature does, you typically use fewer resources. When you design systems based on biological principles, they tend to integrate better with natural systems. But the primary motivation for a Chief Innovation Officer should be performance: finding solutions that work better than conventional approaches.

What This Means Monday Morning

Translating biomimicry understanding into practice starts small. Pick one current innovation challenge. Spend an hour researching how nature handles similar functional requirements. You’re not looking for a complete solution. You’re looking for a different angle, a question you hadn’t considered, a principle that might apply.

Build relationships with people who understand biological systems. Not necessarily to hire them, but to have conversations that bridge domains. Universities, research institutions, and specialized consultancies can provide this kind of knowledge translation.

Create permission for your teams to explore biological solutions to business problems. This sounds obvious but often isn’t. People need explicit encouragement to spend time on approaches that might seem tangential to immediate deliverables.

Most importantly, recognize that biomimicry isn’t a special innovation tool you pull out for specific projects. It’s a lens that changes how you see all problems. Once you start noticing how nature solves challenges similar to yours, you can’t unsee it. The question shifts from whether biological principles apply to your work, to which ones apply and how to implement them.

The Long Game

Evolution operates on timescales that make corporate planning horizons look like eyeblinks. But it produces solutions with remarkable longevity. Many biological mechanisms have persisted for millions of years because they’re fundamentally well designed for their functions.

This suggests something about the quality of innovation that biomimicry can produce. Solutions based on deep biological principles aren’t just clever. They’re robust. They work across varying conditions. They often solve multiple problems simultaneously. They tend to age well because they’re based on fundamental physics and chemistry rather than temporary market conditions.

For Chief Innovation Officers facing pressure to produce quarterly innovation wins while building long term competitive advantage, this dual quality is valuable. Biomimicry can produce both: innovations that work now and continue working as conditions change.

The barrier isn’t complexity or cost. It’s attention. It’s taking the time to look at nature not as scenery or metaphor but as a technical library. It’s being willing to learn from 3.8 billion years of research and development that happened to produce every living thing around us.

Your next breakthrough might not come from your industry. It might come from a beetle, a termite, a coral reef, or a spider.

The question is whether you’re paying attention.